Most of the early reports of Dartmoor Prison paint a stark and sombre picture of prison life behind those imposing granite walls. But here is one from 1909 that almost reads like an advert for the gaol which could have appeared in a travel magazine. Clearly Mr. B. T. Bridges was given a tour of the prison by its public relations officer.

“I had rather be in a balloon above the clouds. I had rather do a five years stretch anywhere else than three years here!” – a Dartmoor convicts’ comments to the Home Secretary, 1900s.

“It is curious how convicts hate Princetown Prison more than any other in the country, worse even than that bare peninsula of Portland. The air is splendid, the climate though wet, is not severe, the buildings, if gloomy, are airy, well warmed and comfortable, the officials are as considerate and the food and treatment as good as at any other prison in the country. Yet the fact remains that the average convict’s statements are those expressed in the first paragraph of this article.

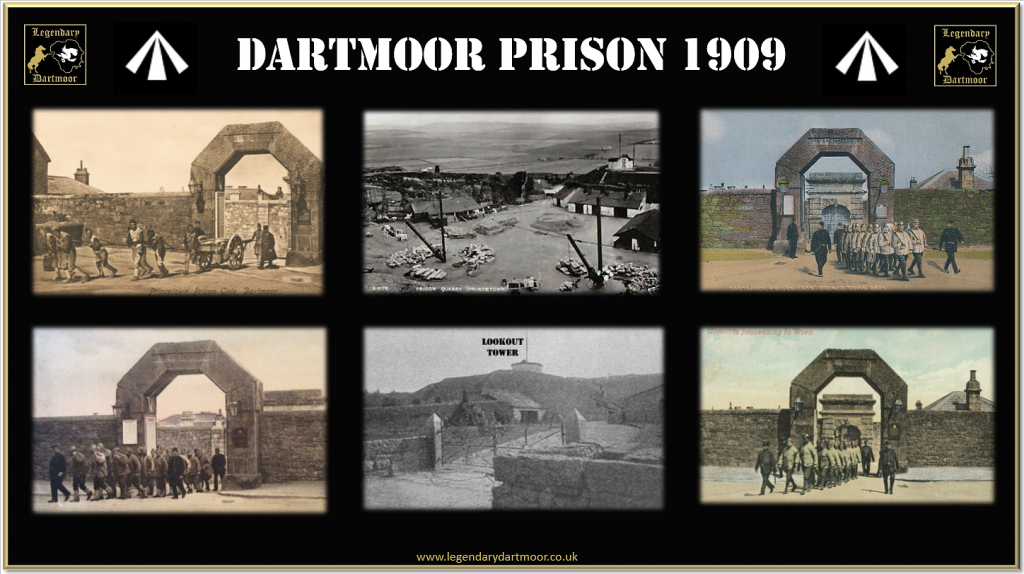

The explanations seems to be that Princetown is one of the most isolated villages in England. Although it has a railway, it is seven miles from Tavistock, the nearest town, and seventeen from Plymouth. The average convict being a town-bred man, this isolation appals him. The great sweeps and stillness’s of the beautiful moor do not appeal to him. Walk up the one long street of Princetown from the station to the gaol, and you will see that the whole place is but an outgrowth of the prison. Warders in their dark blue uniforms walk rapidly up and down. Convicts in ugly drab are at work on new prison buildings. Very likely you may see a party of men in blue coats busy in the street clearing the drains. These are not clean-shaven like the ordinary convict. Some of them have beards almost grown. These are the last few weeks of imprisonment, during which they are allowed to grow hair both on their heads and faces.

Dartmoor is a very large prison. There are in all about eleven hundred convicts, including a considerable number of J.A.’s or juvenile adults, who are kept completely separate from the older men, and whose discipline is more that of the reformatory than of the convict prison. To look after these eleven hundred prisoners there are about one hundred and fifty warders and civil guards, who watch the labour gangs at work and prevent escape. Of the latter, a certain proportion are mounted. You can tell at a glance the status of a prison officer by the letters on the shoulder of his uniform. “A.W.” means assistant warder, “W.” warder and “C.G.” civil guard etc. Among the officers, discipline is that of the army. They salute their superiors and address them as “sir.”

Dartmoor has many industries, but it is pre-eminently the farming prison. The farm granted by the Duchy of Cornwall is more than two miles in length, and covers some 2,000 acres. Most of it is pasture, and the prison is famous for its horses and sheep. Wheat will not ripen on Dartmoor, but oats are grown, and also excellent turnips, cabbages, and other vegetables. Prison celery has a well deserved reputation for excellence. The industry second in importance to farming is granite cutting. There is a large quarry in the side of Hessary Tor, and the whole prison is constructed of material cut from this vast pit. – see Herne Hole Quarry

Up above the quarry is a stone watch-tower with signal post fitted with semaphores. There is another similar tower on top of the prison itself. All day long, when gangs are at work outside, a warder stands in each of those towers sweeping the country with a telescope, and receiving reports by signal from parts far away on the outer edges of the farm. There is a regular code of signals; but these, of course, are secret. One signal, however is familiar to all. When a warder on duty stops and raises his right arm it means, “all correct.” To make assurance doubly sure, there is an elaborate system of telephone wires running across the farm in several directions. At any point where a gang may be at work a receiver is attached to the wire, and at the first sign of any disturbance, news is instantly sent to the prison itself. With all three precautions, and with the additional guard of miles of treeless moor on every side, it is wonderful that any prisoner can be fool enough to bolt. It is said that within the past forty years only one man has ever made good his escape from Dartmoor.

At Dartmoor the prison day begins with the ringing of a bell at ten minutes past five. At half-past five the officers come in. Breakfast is served at a quarter of an hour later, then the men clean their cells, and at seven are marched to the chapel. Service is very short, and at a quarter past seven the men turn out for parade. Each goes to his proper gang in which he takes his usual place. The gangs are numbered, and the men are ranged according to height. Now comes the operation of searching each prisoner, the convict standing with arms outstretched, cap in one hand, handkerchief in the other. The searching, or “rubbing down” is very rapid, and by half-past seven the day’s work is under way. Some gangs are marched out on to “The Bogs,” as the farm is called; some to the quarry; others to building gangs, for there is nearly always building going on at Dartmoor. The latest work has been the construction of a number of new warder’s houses.

Each shop has its gang. There is a large tailor’s shop, where all the clothes for the convicts and all the uniforms for the officers are made and repaired. As you enter this room you are conscious of a low hum, yet you never see a lip move. Old lags keep up a constant whispered conversation without ever moving one muscle of their face. The tin shop is one of the most important establishments at Dartmoor. Here are made the utensils, not only for Dartmoor, but for all the other great convict prisons in the country. There is a cobblers shop, for making and repairing the prison boots and slippers. The modern convict, it may be mentioned, is provided with slippers for use in his cell. There is a blacksmith’s shop for repairing the farm and quarry tools, and a shop for making mail-bags for post office use. There are also basket-making and carpenter shops. As far as our present laws allow, the prison is self-supporting. It grows its own vegetables, has its own milk supply, makes and mends its own furniture, clothing, tools, and machinery. It has its own gas plant operated by convicts, its own laundry, while its kitchen and bakehouse, models of cleanliness, are operated by convicts under the tuition of skilled warders. Even the books in the prison library are re-bound in prison. The gangs return from work at ten minutes past eleven, when after counting and another “rub down”, they are taken back to their cells for dinner. They do not go back to work till one o’clock, and as the day’s work is completed at five, it is easy to see that the convicts’ lot so far as hard labour is concerned is not half so severe as many free men.

The Dartmoor convict who behaves himself suffers few real hardships, beyond the loss of liberty. He is well fed on good, wholesome food. He lives in a warm, well-fitted cell; he has a comfortable hammock or cot, he is not overworked, and his health is well looked after by two competent and kindly prison doctors. If he is under forty he gets schooling. Numbers of men learn to read and write in Dartmoor; he is taught a trade if has not got one, and he is allowed to earn a little money. In a five years’ sentence he can, by good conduct, leave with four pounds in his pocket.

There are certain jobs at Dartmoor, as at other convict prisons, which are given only to men of proven good conduct, and which are greatly coveted. These are such as bath o kitchen orderly, gardening work, and certain farm jobs such as milking. There is hardly a case on record of one of these orderlies forfeiting his privileges by bad conduct and is seems almost as if more a convict is trusted the more worthy he strives to prove himself of the trust reposed on him.

The great majority of convicts at Dartmoor are distinguished by their amazing appearance of health. Men arrive, wretched, pallid, broken-down weeds, and in a few months are converted into fine, muscular, bronzed specimens of humanity. No doubt this is partly the result of regular hours, no smokes or liquor, and good plain feeding. But much credit must also be given to the splendid moorland air – the finest in England south of Derbyshire.” – B. T. Bridges,- The Penny Pictorial in The Gazette, April 10th, 1909.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor