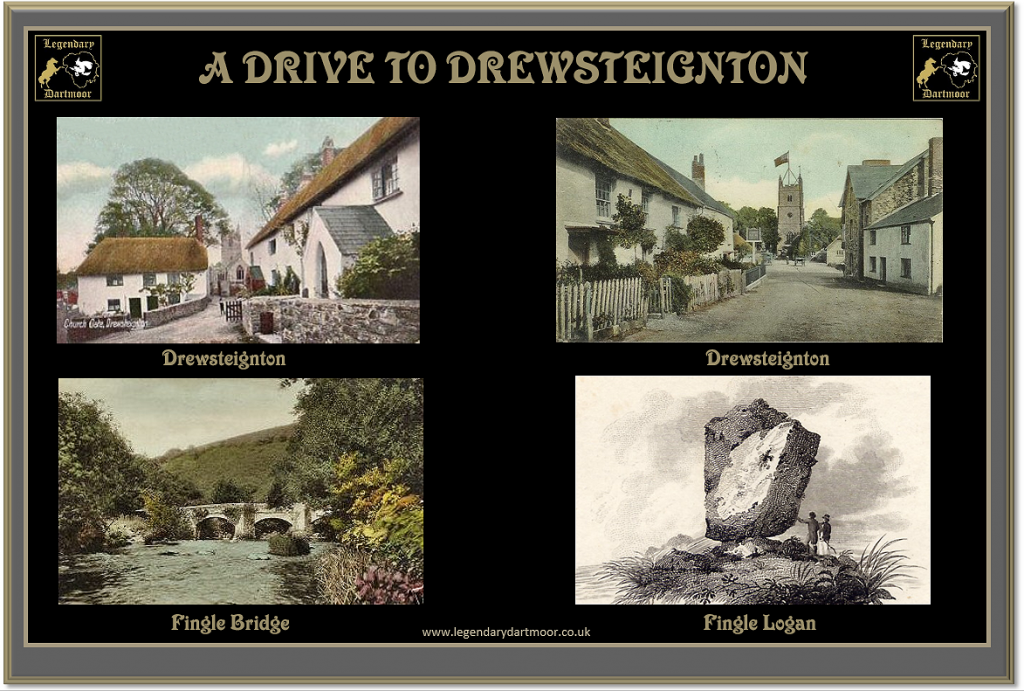

Here is an account of a man’s visit to Drewsteignton in 1848, as always some of what he saw is still visible today but also much has been lost in time. Obviously the church is still there along with all what is described in his visit. The “New Inn” is now the “Old Inn”, the time honoured Fingle Bridge can still be admired but Farmer Smith’s clover and potato fields are long gone.

“The small village of Drewsteignton occupies a retired position about a mile to the left of the great Cornwall road from Exeter, after it passes through Crockernwell. Were it not for its old English aspect, its rude and primitive appearance might suggest to the tourist the impression that a century had hardly elapsed since its first erection in the midst of the wild, as a centre for the population engaged by necessity or accident in the reclamation of the soil. The narrow lane which forms the main road into it, ascends a steep hill (at the bottom of which a brook crosses the highway), and abruptly turning the projecting corner of a cottage, terminates in the village “green,” now green no more, which includes withing itself the requisites of a promenade for the old people on Sunday evenings, a play-ground for the children after school-hours on working-days, and a situation always vacant for strollers’ booths when the welcome “revel” time – once a year- comes around. The few houses cluster together on the sides of the open space which they almost enclose, one end of it forming an entrance to farmer Smith’s clover field, and the other being bounded by a stile, which admits the pedestrian into the quiet churchyard, where, “the rude forbearers of the hamlet sleep.” In a district where human habitations are so few, and for the most part, mean in their accommodation, the wayside commercial inn assumes an air of importance and propriety. The simple and unsophisticated habits of the Drewsteigntonians are bespoken from the fact that there being no less than three of these caravansaries established in their pretty town of twenty houses, and the only apparent buildings for secular business. The ancient of these which still bears the appellation of “The New Inn” is kept by Farmer Smith, the biggest man in the parish, and whose state is only approached by that eminent arbiter of rural disputes, the parish constable. The happiness of a retired village where there is but one surgeon and no lawyer, may indeed be envied, and the venerable church, seen beyond the stile before mentioned, throwing its projected shadow upon the hamlet, “like a hen gathereth her chickens,” seems as if it were the tutelary guardian of the peaceful place.

It was at the end of a week of wet days in August that I and some friends travelling, like the famous Dr. Syntax, “in search of the picturesque,” mounted a four-wheeled vehicle, and started for Drewsteignton. The sky was lowering with clouds, and nothing but our faith in a strong “Nor-wester” which was blowing, would have induced us to quit our dry hearths under such an inauspicious circumstances. We had the benefit of a slight sprinkling as we neared Taphouse, – but our arrival at Crockernwell, a small allotment of blue sky, “enough for a pair of Dutchman’s breeches,” as the old saw hath it, preceded the gradual restoration of the azure vault to perception and animated us with the greatest confidence in the accuracy of the sage maxim aforesaid. Among the “lions” of the neighbourhood of Drewsteignton are “Fingle Bridge” upon the Teign, and “Logan Stone.” To these romantic spots we hastened, after having partaken of Friend Smith’s nut brown ale, and substantial bread and cheese.

To appreciate the full beauty of the romantic bridge of Fingle – the records of those whose connexion with the district must have been lost with the Druids – it should be viewed from the lofty summit of the hill immediately contiguous. The spectator looks down a precipitous and dizzy height of several hundred feet – and, if he has sufficient presence of mind to prevent his hat from being blown into the chasm, perceives spanning the narrow and rapid river the antique bridge of grey stone – which at a distance appears a fragile toy scarcely wide enough for human foot to rest on. You have just time to become enraptured with the view, and to loose your power of respiration from the mountain breeze, when your guide springs, like a swift gazelle, down into the depths of the yawning abyss, and leaves you to follow. Some of your adventurous companions rush after the treacherous pioneer. In tremblingly attempting to follow you slide gently down into a prickly seat of furze, and discover to your horror that the hill-side abounds with huge sharp edged stones concealed beneath the vegetation, which graze your shins, and threatens to trip up your heels. In the declension of the party towards the river various accidents occur. One inpersonification of a prudential career sliding down the steep, has the ill-luck to lose his fly-book from his coat pocket, picked up by an obstinate furze bush. Several hats and caps illustrate the laws of gravitation, as do also more than one of the wearers, and after a very undignified descent, the whole party assemble at the foot of the Devonshire Alps, consoling themselves that no bones were broken. Crossing an arm of the river by means of a pole placed across – a rustic accommodation which proves a trap for the uninitiated, who are sure to slip into the stream – we reached the bridge; and after a critical survey of the masonry, for which Mr. Whitaker, the architect of the county bridges, must feel deeply indebted, or guide – who seemed to have no conscience for the asthmatic – hurried us off to the Logan stone, situate, as it turned out, some two miles higher up the river. The path which skirted the water’s edge, and more than once crossed the aqueous boundary, was at first attractive and easy. Traversing the borders of verdant plantations, which cover the steep hills on each side of this part of the Teign, the walk promises a continued grove, and the quiet repose of the woodland in the sunlight seemed to realise those descriptions of the Minstrel of the North, which are vivid in the remembrance of the readers of Ivanhoe and Rob Roy.

But the increasing difficulties of the track soon drew our attention from surrounding objects to the important point of securing our footing at every fresh step and keeping dry-shod. The Teign gushes along over a rocky bed similar to the substratum of the hills whose sides merge into it; and the river would seem to have occupied an opening in the solid granite formed by some remote convulsion of nature. Its channel traverses what is indeed a valley of rocks, which mark the wandering of its course with angular projections, just affording lodging for a stunted shrub of Goat’s Foot. Beyond these corners the towering hillside gently recedes, embosoming some emerald glade where Robin Hood would have gloried to revel, or Friar Tuck might have complacently enjoyed his venison pasty in days of yore. The romantic however is taken out of you by the stern realities of wet stockings as you flounder over granite blocks and brackish brooklet, through groves of brambles and bowers of besom, to the great depreciation of your personal beauty, and incalculable damage to your ventilated gossamer. As for your guide, he only acts as Will o’ the Wisp, leading you into innumerable difficulties, without vouchsafing to lend you a helping hand out of them; but this you feel to be a compliment, as he evidently gives you credit for “knowing all about it.” All events he knows how “to keep his distance,” for he is never less than a quarter of a mile in advance, unless specially hailed.

The logan stone is another surprising specimen of Druidical mechanics. It is – or rather was – poised so accurately, that the immense block could be moved by the touch of the finer. Former travellers have acquainted the world with the indubitable fact that this quality no longer exists no longer. But our host, who furnished us with our stalwart Saxon guide, informed us at the same time with conclusive nod that he “wud mak’n move.” We were thus buoyed up with the idea that the mantle of the Arch Druid of old had been caught in its descent by the ancestor of the worthy occupier of the “New Inn,” who had transmitted it undecayed to the present generation, and now we should witness what had been denied to less favoured eyes – the huge mass oscillate obedient to the magic touch of the wielder of this mysterious power. We were considerably disappointed to find that the only mode by which the guide could make the stone “log” was by clambering up in proprid persona to the summit, and then exerting all his physical force by means of jumping and stamping upon the least supported end, to force it to dip; which it did perceptibly.

Beyond the logan stone we observed the bed of the river by the Moretonhampstead bank, a large block of granite laid across upon two upright stones of the same description. In the transverse block some iron bands had apparently been inserted. My friends, who were great antiquarians in a moderate way, were about to deduce from this circumstance a contradiction to the notion of some writers, that mining operations were unknown to the ancient Druids, when the guide quashed the argument, which was beginning to grow warm, by informing the party that the iron had been put on by a former curate of the parish who had found it minister to his convenience to form a wooden footbridge across the river to save a mile and a half distance between his house and the parish church.

In ascending the hill-sides on the return to Drewsteignton the view is one of the most romantic and beautiful which can be conceived. Far beneath, the Teign pursues its winding course like a silver thread through the narrow gorge which nature has marked out for its rocky channel, and in the distance through the opening is seen Chagford and the high tors of Dartmoor. The walk you are pursuing traverses a magnificent natural carpet, which the glowing tints of the purple heath and the golden furze fill up and adorn with variegated and burnished splendours. A potato field occupies the summit of the hill, and having crossed it you behold the pretty church tower of Drewsteignton crowning the opposite eminence. A visit to a country church is always interesting, sometimes painful. The feelings inspired by a view of the interior of Drewsteignton church, however, partook of none of the latter quality. It appeared to be neat and clean, though small, and the substantial shutters which the churchwardens had provided outside for the protection of the east window showed that its requirements were not neglected. On these being opened, a painted window, representing the Redeemer’s Ascension, and executed in a very credible manner, became visible. The countenance was exceedingly good, and rivetted the beholder’s attention from the indescribable softness and benevolence which formed its expression. Another curiosity in this church is an old escutcheon above the south entrance, representing the Arms of Queen Elizabeth, with the letters E. R. This was, no doubt, placed there in the reign of that sovereign.

Having seen all these attractions, which I have vainly attempted to describe, we turned our footsteps – rather weary with our unwonted and exciting stroll – in the direction of the hostel. The keen mountain air had sharpened our appetites, by which viands far less palatable than those substantial dishes which graced farmer Smith’s well furnished table, would not have been rejected. Necessary refreshment ended, our horse was again harnessed to the vehicle, and we returned well pleased with the gratification our “drove” had afforded.”

The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, September 16th and 23rd, 1848.

If you would like a modern version of this walk I did please see here – Teign Trundle.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor