“In one of the most lovely spots in Devonshire, or for that matter, the whole of England, is a romantic little village, it lies distant, secluded, still in a fruitful valley, little known, and less troubled by the outer world. It is a veritable Eden, where peace and plenty seem to reign. For nearly twenty years the labourers have not had a pauper in their midst! They are free from the care of a resident policeman; they have no public house: no clergyman resides among them; and there is no dissent! So ideal a country village deserves to be better known and to have its fame spread abroad as an example to other places. One hears so much nowadays of the hard and depressed lot of the agricultural labourer that it is absolutely refreshing to alight upon such a place in which he seems to have no grievance and in which he and the squire live on perfectly friendly terms. A visitor to the spot soon learns that the squire was at the root of all this content, if not bliss.

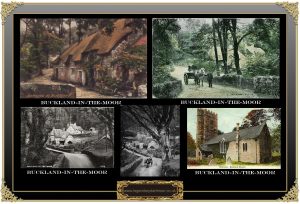

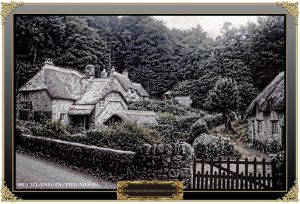

The squire owns the whole of the parish except one small estate which is in trust to provide funds for repairing the church, and though he only farms about 50 or 60 acres himself all the labourers seem to owe him allegiance. The farms are mostly small, and the farmers are able able to work them with only occasional assistance beyond that provided by their families. The story goes that the squire is most kindly with his dealings with his tenants. One of them had two small farms, and with advancing years they appeared to be getting too much for him. At any rate his rent was in arrears. He was summoned to the “house,” the squire told him he better give up one of the farms, and the back rent was forgotten. All the labourers live in the squire’s cottages, pretty, old-fashioned thatched houses which peep out here and there by the roadside from amid the most perfect woodland scenery. They are in no sense modern. Though the difficulty of getting reed for thatching increases year by year, there has been no introduction of slate and tile yet; and may such reminders of the town be kept out.

On enquiring whether any particular system has been adopted by the squire for keeping pauperism at bay, nothing was known about the system. Nobody was at want and that was enough! But though there is no hard and fast “system,” the best of means are adopted for keeping the men and their families independent. The ordinary labourer is paid 15s to 18s a week, and most of them get cottage and garden rent free. Those who go through the form of paying rent get 1s. a week extra. At harvest time the labourers get extra pay as well as cider, and in the spring they are employed in piece work “rinding,” the trees in the coppices. When the farmers want a hand the labourers make their own terms with them. They do not care for large allotments, and appear to have no desire to try to live on small holdings. As one man aptly put it, “Us can’t get on without a Saturday night to go to,” meaning that they must have their their weekly wage as a mainstay. It will thus be seen that the position of the labourers in the village is better that that of thousands of men employed in towns, railway porters and such like. With house rent, garden and other extras none of the labourers are getting less than 18s. a week. But that is not all. If they are ill at any time and are kept home a week or ten days they get their wages just as though they were at work. If they are incapacitated for a lengthened period of course they call on their clubs for support, and get 8s. or 10s. a week allowed. Then the squire, recognising that in times of sickness they want at least as much as when well, sends down every week sufficient to make the amount received equal to the wage that would have been earned. If they had been earning 16s. a week and received 10s. from the club he allowed another 6s. To those who happen not to be in any club he allows half pay.

“But what happens to those too old for work?” was asked of one of the villagers. “They are never too old out here.” Most of the old folk die in the harness. When they are past work they are kept on the pay list and potter about doing whatever they can. There is none of the rush and callousness of life which throws an old man aside for a younger man. Widows seem to be unknown there. One naturally enquired what became of wife and children when the husband died, but no case of a husband dying and leaving a widow and children was remembered. There is little need for charity under such circumstances. And yet there is a clothing club. The squire formerly maintained it, but as there was no use for the church offertories, that money has of late years been applied to the club. The last paupers one could learn of in the parish were two old sisters, who, many years ago had pay from the Union, but were allowed a cottage rent free. Naturally there are not many changes in such a village. Those fortunate enough to live there are wise enough to see when they are well off; and so, for the most part, they live on year after year, their uneventful though nevertheless happy lives. They have no public house, and do not seem to require one either for thirst-quenching purposes or as an evening resort. After work is done they are glad enough to get home, do their bit of gardening, have a pipe and read, and then go to bed, for they have to be out early in the morning. The labourers are rather proud of the fact that they have neither “passon nor policeman.” They have a small ancient church, and a graveyard in which there are singularly few tombstones.

Another remarkable fact about the village, concerning which it is probably unique, is that no parent residing there has ever been summoned for not sending his children to school. No special inducement is held out either to the children or parents, but the fact remains that the children attend remarkably well and pass good examinations. Some of them live as far as two miles from the school. The village has enjoyed free education from time immemorial. The present squire’s ancestors built a school many years ago, engaged teachers, and had the children taught free of charge. An elderly resident remembers the “dear old boy,” who taught the children as far back as he can recall. She only taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and knitting. There was on old man in the village,”a curious old fellow,” who wrote with a most beautiful copper-plate hand, and he kept a night school in which writing was taught as a luxury. When the education act was passed the present squire had to build a new school; but he continued, like his predecessors, to provide free education. It is interesting to learn that despite this training, superstition still prevails in the village, and that now and then a labourer of his friends got “overlooked.” The cure is a journey to a “white witch,” in the district, concerning whom we might have something to say on a future occasion.” – The Clifton Society, August 19th, 1897.

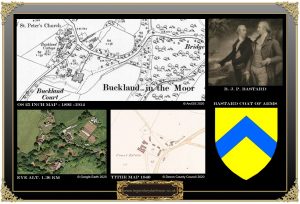

So who was the very philanthropic squire? The Lord of the Manor was Baldwin John Pollexfen Bastard (1830 -1905) whose main seat was Kitley House. He served as a Tory member of Parliament from 1783 to 1812 and also served as a colonel in the East Devon Militia. In the Buckland-in-the-Moor 1861 census there were 113 inhabitants which included seven farmers and 1 blacksmith.

At the time of writing this we are in the midst of the Coronavirus pandemic and in the UK many people are unable to work and concerned if their employers will pay their salaries. This current situation certainly puts into context the security those tenants must have felt way back then – free rent, free garden to produce their own vegetables etc., a healthy environment and no closed pubs to worry about.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor