The Grey Wethers – version one

About a hundred and fifty years ago the small moorland farm below Sittaford was renown for its sheep, the holding had been in the family for generations and now the latest of the line was carrying on its traditions. They had a very pretty daughter called Felicity who in her twenties was causing concern because there was no sign of her marrying and settling down. She would spend all her spare time walking the northern fen which definitely was not the place to meet any eligible men. Sadly one day their old shepherd died, he had worked for the family for longer than could be recollected so clearly he was sorely missed. However the sheep needed tending and a new, younger flock master was employed. He was called Jan and came from near Moretonhampstead. It did not take long for him to fall in love with Felicity, and on her part, fearing being ‘stuck on the shelf’ she decided that although he was not what she had dreamed he ‘ud doo’. So Jan set about building a cottage down in the Cleave. Felicity turned her labours to filling ‘the bottom draw. Time moved on the and cottage grew and the draw filled until soon a date was fixed for the wedding, the parson was summoned, food prepared and a fiddler booked.

A few days before the wedding Jan was coming back from ‘Moreton’ way when over his left shoulder he heard the cuckoo call. Now this was one of the worst omens possible and it greatly worried Jan. That evening he took Felicity down to the completed cottage. She was delighted, everything was ready, the roof tightly thatched, there were bunches of straw at each gable end to ward of witches and pixies, every key had the obligatory holed ‘hext stone’ tied to them, again to ward of witches and the garden planted with every herb and flower imaginable. The future was looking good. The next day Jan drove the flock up to the pastures on Sittaford tor, the farmer and his wife had gone to Peter Tavy to buy the cider for the wedding, Ned the old farm hand had gone cutting peat and Felicity was sat on the doorstep sewing a lace pillow case. She had nearly finished the pattern when one of the threads broke and the bobbin fell to the floor. She stooped down to pick it up when to her amazement she saw a noble young man on a magnificent horse stood at the gate. It seemed as if he had ‘dropped from the blue’, which means nobody knew from whence he came. He may indeed have been a prince or lord or even the Devil himself but all accounts agree that he ‘wor a fureigner’. Old Benjamin the hedger swore blind the strangers horse had wings. But either way legend decrees that he was handsome and no maiden could have withstood his charms for long. Felicity did resist for at least half an hour for that is the length of time Benjamin reckons it took for her to hastily gather some clothes and then mount his steed and ride off with him. Despite all efforts she was never seen again.

To say Jan was distraught would be an understatement—he was inconsolable and the blame was put squarely on the shoulders of that ill fated cuckoo which he heard in the lane a couple of days previous. So from that day on Jan shunned all human contact and spent all his time with his flock.

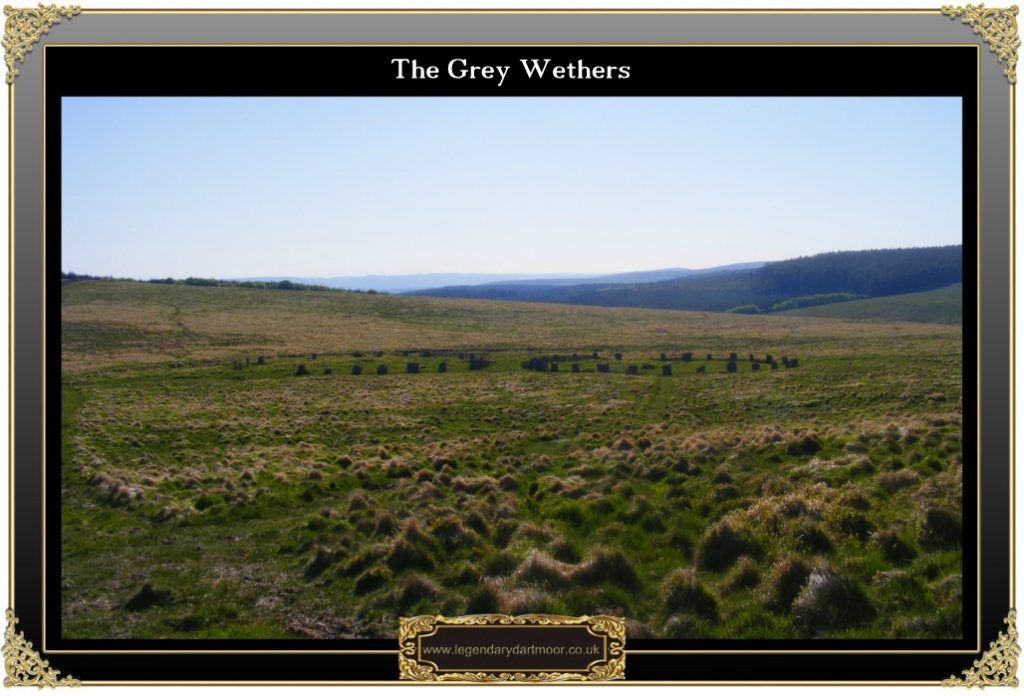

Now Hu, the old god who lived on Sittaford tor noted what a good shepherd Jan was and how unhappy he was when away from his sheep, so he turned Jan and his flock into a group of stones so as they could never be parted again.

To this day the petrified shepherd and his sheep can be seen on the side of Sittaford tor—they are called The Grey Wethers and act as a lasting memory to The Faithful Shepherd. It is also said that every May when the first cuckoo call is heard on the moor, Jan resumes his human form and he and Felicity wander hand in hand down to the site of a ruined cottage.

The Grey Wethers – version two

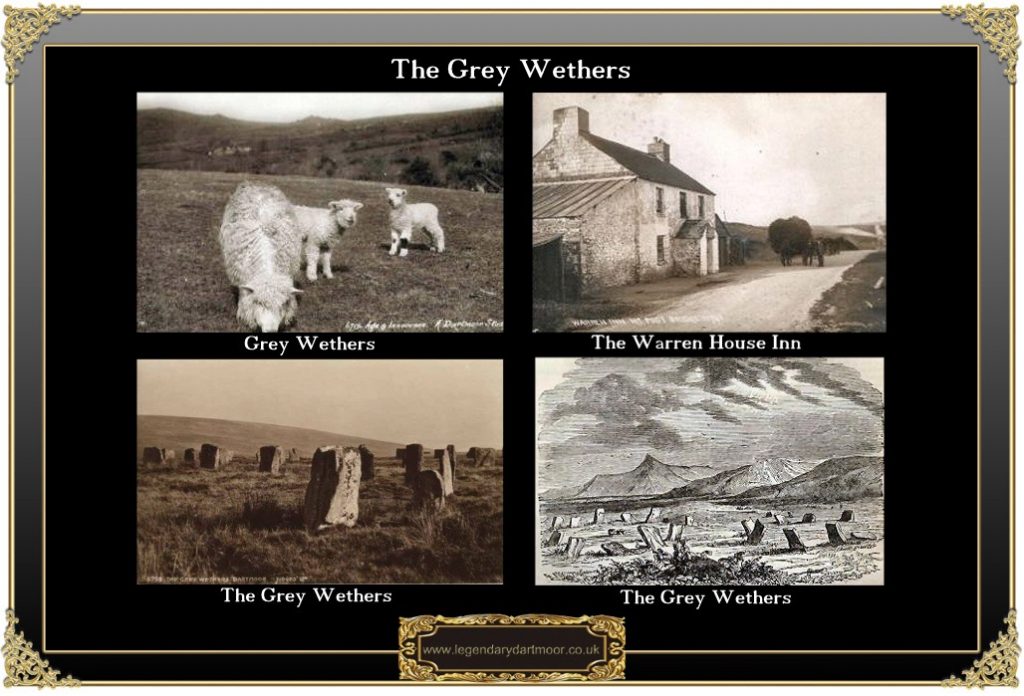

Again back in the 1800’s a new farmer appeared in the locality and made known his intent of becoming the most prosperous landowner on Dartmoor. One misty autumn day he rode to Tavistock market to purchase the first of his new flock of sheep. However to his disgust and to the chagrin of the local farmers he decreed that all the sheep for sale were “totally useless and their breeding was the result of bad husbandry”. So on the way back he called into The Warren House Inn to drown his sorrows, with the aid of some of the local cider he more than accomplished. On relating his wasted market journey to the assembled company he was surprised to hear that one of his fellow drinkers had in fact an excellent flock of sheep grazing nearby which he would be prepared for a ‘gud price, mind’ to sell. So after a few more ciders they rode off over Water Hill to inspect the sheep. However as it was a cold misty day they only went as far as White Ridge which was far enough for the farmer to see a fine flock of sheep grazing below Sittaford tor. Delighted with his purchase he quickly made his way back to the inn to seal the deal with some more cider. Sadly however, the next day when he went to collect his new flock he discovered that what he had seen in the mist of the moor or more aptly the mist of cider was in the cold light of day two circles of stone or two circles of Grey Wethers as they are called today.

The Grey Wethers – version three

One warm summer Sunday a group of local boys decided they would have a game of football, so to avoid the wrath of the local preacher they made their way up to the moor to find a suitable pitch out of sight of any prying eyes. Soon a flattish area under Sittaford tor was selected. Jackets were became the goal posts and ponies reluctantly became the spectators. The game was in full cry when a flash of lightening crashed down from the cloudless skies and the footballers were turned to stone.

The Grey Wethers – version four

This tradition is a much shorter tale than the rest, it is simply that at sunrise all the stones turn around to greet the dawn.

The Grey Wethers – version five

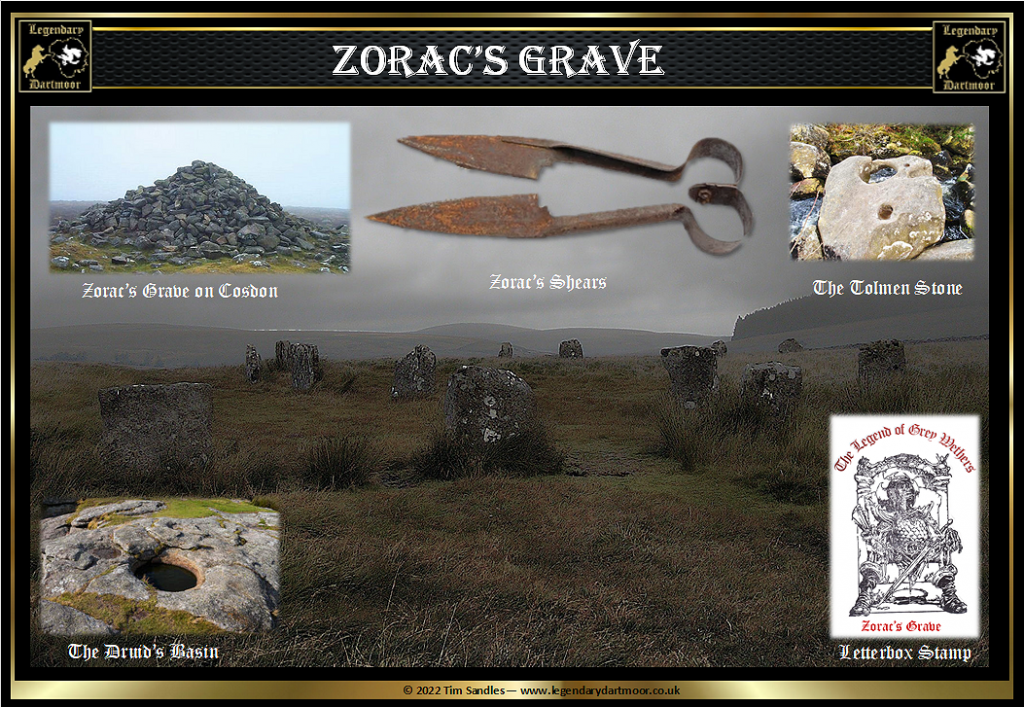

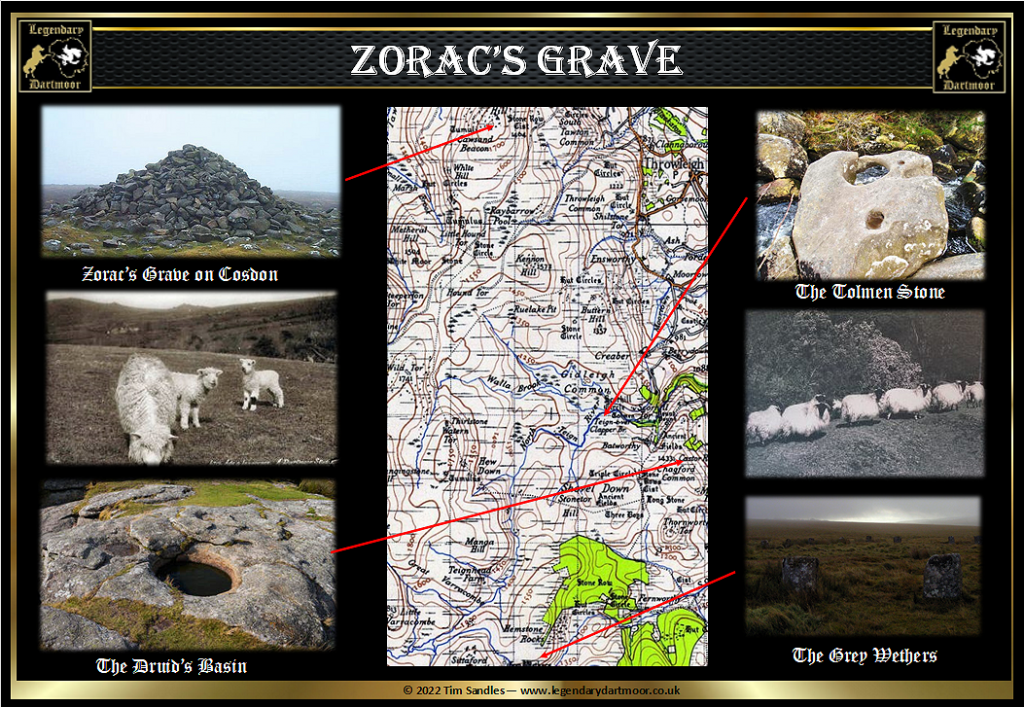

This story is about three peatcutters who were working the summer on the moors cutting peat for sale in the winter. They used to spend weeks on end working and living on the moor. Home to them was a tiny crude stone built shelter. It has been suggested that they were living at Statt’s House which is now a small ruin high on Winney’s Down. There were three cutters living in this small hut, two old local peatcutters and a younger ‘blow in’ (stranger). One night having eaten their supper of mutton and potatoes a mighty storm blew in. The rain was lashing horizontally, blown by a mighty wind, thunder crashed all around and shook the threadbare thatch on the roof. The men huddled around the small fire and the two ‘old boys’ started talking about the Grey Wethers. They happened to mention that if anybody could shear them they would be rich beyond all dreams. This made the stranger inquisitive and so he asked to be told the story. The two local men related how centuries ago a peasant called Zorac lived nearby and kept a flock of sheep. He worshipped Belus the Sun God who smiled kindly on Zorac. Over time his sheep did well and he became a wealthy man. It was the custom that the followers of Belus were expected to make midsummer sacrifices of thanks to the God. This particular year all of Zorac’s sheep were thriving and when he came to find the smallest one he was grieved to see that they were all fine strong animals. Zorac had become a greedy man and so he decided to steal a lamb from one of his neighbours and offer that as his sacrifice. Pleased with his deception he took the stolen sheep high up on to Sittaford tor and paid his homage to Belus. Belus was an all seeing God and he knew what Zorac had done and so decided that retribution would be divine. When Zorac returned to his flock he saw to his absolute horror that the sheep had been turned to stone, and they now stood petrified in two perfect circles of stone. From that day on Zorac’s fortunes took a dive and he soon became a poor desolate soul. Slowly his health deteriorated and after a month of suffering he shed his mortal coil. His neighbours were not sorry he had died but out of pity they buried his body beneath a cairn on Cosdon Hill. It became an annual event that every Midsummer Eve the sheep returned to life and grazed the the grassy slope of Sittaford until the first rays of sunlight broke over the moor, then they were turned back to stone for another year. The cutters then went on to say that if anybody could shear one of these sheep before sunrise, then sprinkle the fleece with water taken from the Druid’s rock basin which is on the top of Kestor the fleece would turn to gold. The sheep must be shorn with Zorac’s shears which were buried with him in the kistvaen under the cairn on Cosdon. At midnight the shears then must have been dipped into the river Teign where the Tolmen Stone sits. One of the cutters also told how an old rhyme contained the secret of how to shear Zorac’s sheep. He rummaged around in his pack and produced an old piece of parchment and told the stranger to memorise it, which he duly did.

For ages the stranger thought about the quest and the riches it would bring. At first he thought it nonsense but as Mid Summer’s Eve approached his greed began to get the better of him. A week before the sacred eve he had made his mind up that he was going to get the Golden Fleece. So armed with his turving iron he set off up to the lofty heights of Cosdon. All day he sweated and swore as he dismantled the stone cairn. Eventually he came across the burial cist or kistvaen. With his iron he prized off the stone cover and was soon looking into the dark and dank grave. The brilliant white of a crouched skeleton shone out and by its head he could see a rusty pair of shears. His hands shook as he slowly lowered them into the grave and gently lifted the shears out. He was expecting a huge bolt of lightening but nothing happened so he quickly scurried away clutching his prize. Although completely exhausted after his grave robbing he slowly trudged over to Kestor. Here he clambered to the top of the tor and filled his flask with water from the deep Druid’s Basin. Having nearly completed his quest he then slunk down to the river Teign where the Tolmen Stone was located. It was about an hour until midnight and he spent that time sitting in the moonlight working out how he was going to spend his fortune. Midnight approached and he slowly edged his way to the river bank and slowly lowering the shears into the water he recited the rhyme that the old peat cutter had told him to memorise: “At midnight by the Tolmen, upon the river Teign, The shears within its water, shall carve thy weal or bane. Strike on thy left, then on thy right, red blood the flood shall stain. Beware lest trembling fingers, withdraw the blade again, But hold it firmly neath the stream, till tress of hair appears, Which seize and keep to bind the sheep, then use the magic shears.”

The water began to boil and bubble and a huge solitary black cloud passed across the moon, the air turned cold and a lone, low wailing sound wafted down from the moor. The wailing grew louder until a voice could be heard, “Strike! Strike! Crimson blood shall stain the flood and whet the glistening blade that shears the sheep.” Shaken witless the stranger pulled the shears out of the river and as he did so the seething torrent turned blood red. He then gathered his wits and recalled the rhyme and realised he must once more plunge the shears into the bubbling red broth. As he did so the voice boomed out again: “Strike! Strike! See there before thee in the stream, to bind the sheep, fair tresses gleam.” No sooner than the mysterious voice had uttered those words a long tress of glistening black hair floated past him, in desperation he lunged out and managed to grab a handful of the magical locks. The rest of the tress slowly floated out of his grasp seawards down the river. Dripping with blood stained river water he made his way back up to Statt’s house to rest his weary body and fuddled mind.

Mid Summer’s day was spent cutting peat but as soon as the sun sunk behind the moor in a splash of orange he headed off towards the stone circles. Finding a comfortable clump of heather the stranger took the chance to rest his weary work worn body. It was a warm night and the scent of the heather soon sent him to sleep. He was suddenly awoken by the sound of bleating sheep and as he roused himself he could see that the stones had vanished and in their place were 40 sheep grazing on the lush moor grasses. He grabbed the shears and the twine he had woven from the tress of hair and raced off towards the nearest sheep. After a frantic chase he managed to catch it and loop the short twine around its next. Immediately the sheep stood still. He flourished the shears and began shearing. In his mind he was calculating the value of each piece of fleece he cut off, a smug smile spread across his face as another clump of wool fell to the ground. He then noticed that the sun was beginning to rise over the moor, he must have slept too long, vigorously he resumed his shearing but because the twine was too short the securing knots he had tied began to loosen. He cursed himself for not grabbing the whole tress of hair when he had the chance, that would have made a longer and stronger length of twine. The sheep began to struggle and soon had worked itself free and with a leap and kick darted off towards the rest of the flock. The stranger knew he had failed, all that toil and strife for nothing. A final glance up the ridge showed him the first needle like rays of the sun appearing. He then suddenly remembered the water from the Druid’s Bowl, he grabbed his flask and started to sprinkle the water over what fleece he had managed to shear off. Suddenly a pall of darkness grew around him, he slowly lifted his head to see a flock of sheep towering over him. They were immense and slowly they formed a circle with the pathetic form of the stranger huddled in the centre. A voice boomed out: “Thou that seekest to gain the treasure of the dead, shall win the fatal gift the grave doth yield instead.” The following day the body of the stranger was found crushed and mangled beneath one of the huge slabs of granite that formed the circle. The authorities assumed it was a fatal accident but the two old peat cutters knew better.

With regards to the fifth story it is true that in and around Cosdon Hill are many Prehistoric features. There is evidence for numerous settlements, a reave, five cairns on the top of the hill and a triple stone row with a terminal cairn containing two kistvaens located to the east of the hill. Of the cairns on the summit there is evidence that some of the kistvaens had been opened or robbed, Butler 1991 pp 200 -7. The Tolmen Stone also exists and can be found lying in the river Teign

The Druid’s Basin’ as mentioned in the story also exists in the form of a naturally eroded depression or ‘basin’ located on the top of Kestor. Many writers note that prior to 1856 its existence had been unknown. In that year Ormerod discovered it filled with earth and cleared it out. The basin measured 2.28m at the top and tapered down to a diameter of 0.6m, it was 0.76m deep, Crossing, 1990, p.258. It is worthwhile to point out that many of the early antiquarians and writers tended to attribute such features to Druidical worship. Mrs Bray describes a smaller rock basin on top of Vixen tor: “It will not, I hope, be deemed a useless digression to mention what is supposed to have been the use of these rock basins. Borlase, in his Antiquities of Cornwall, informs us that they were designed to contain rain or snow water, which is allowed to be the purest. This the Druids probably used as’ holy water for lustrations. They preferred the highest places for these receptacles, as the rainwater is’ purer the farther it is removed from the ground. Its being nearer the heavens also may have contributed not a little to the sanctity in which it was held.” It is slightly ironical that in this modern age we find the ideas of the early antiquarians so laughable. The very thought that many of the moorland prehistoric features were built by Druids is now deemed at the best quaint at the worst ridiculous. However from an archaeological viewpoint there still is the temptation to attribute any feature that is not fully understood as being ‘ritual’. OK, we now are able to work out by whom and when any feature was built or made but it is still conjecture as to why. Nothing has changed, two centuries ago they clearly had the who, when and why wrong but with all today’s available technology we still can’t get back into the minds of our ancestors to find out why – two out of three ain’t bad?

This legend is by no means the sole property of the Grey Wethers. Examples of people being turned to stone can be found elsewhere on Dartmoor and indeed across Britain. These legends emanate from the 1800’s onwards and seem to provide a reason for how the stone circles came to be. As noted above it was not until the end of the 19th century that people such as Burnard took an interest in them and attempted to find out their origins. Clearly such features were know to be ancient which in itself give them an air of deep rooted mystery and in some respects fear. There has always been some inherent thinking that these ancient sites must be respected and such stories would enforce this tenet in that you never went near them. Also the late 1800’s was a time of strict religious beliefs, a study of Methodism will show that this was a strong religion in many upland areas of Britain, Dartmoor being no exception. Therefore what an ideal way to demonstrate the penalties of ‘breaking the Sabbath’ than to suggest that these ancient stones are evidence of the wrath of God toward people who had dared to dance or play football. Imagine being a youngster living near to the Grey Wethers and being told the story of the boys who dared to play football on a Sunday. Surely every time you saw the stones it would instill the moralistic ideal of ‘keeping the Sabbath holy’.

Personally I am sceptical as to its validity of this tale as most Dartmoor legends appear in several books in some form or another. To date this is the only reference I have found which relates this story. However, as noted above, there are robbed out kistvaens on Cosdon Hill, there is a rock basin on top of Kestor, clearly the stone circles exist and the Tolmen Stone (see separate entry) can be found in the river Teign. In this light it is possible to see where the inspirational elements for the story come from. Logic also says that if the rock basin on Kestor was discovered in 1856 then this legend must date from 1856 onwards, that is assuming it had not been purposefully filled previously. It is obvious that from a moralistic viewpoint the story illustrates the perils of tomb robbing and excess greed and how strongly the local inhabitants held these beliefs. In this story it took a stranger to attempt the so called quest. The two old peat cutters clearly knew the legend and despite the promise of great wealth would not accept the challenge for it had been instilled in them the dire consequences of doing so.

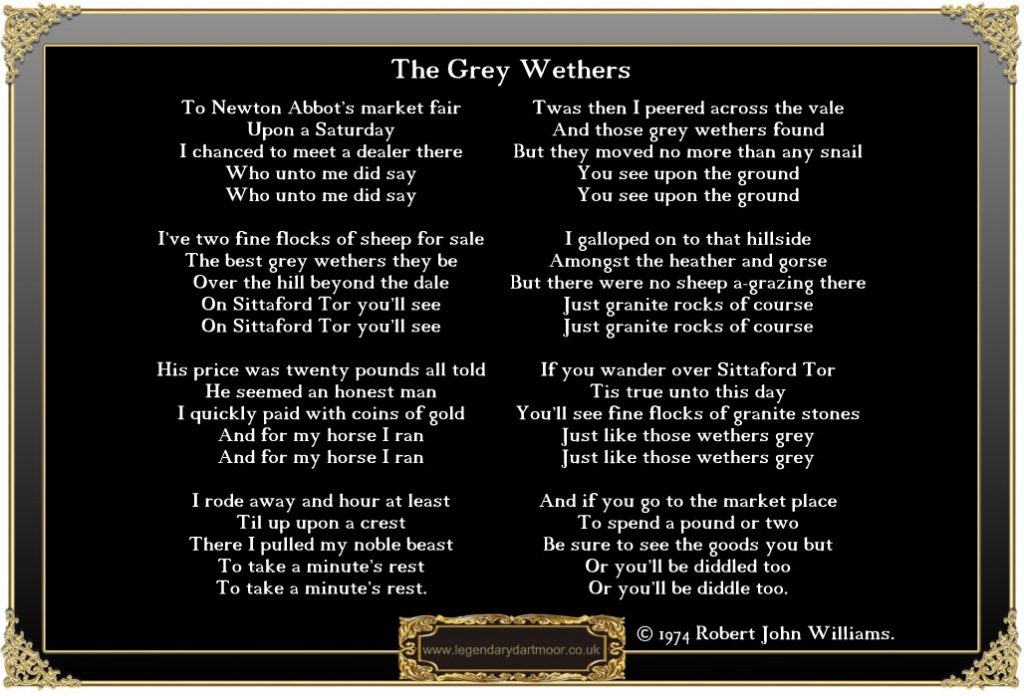

A folk singer from the United States has recently contacted me and kindly sent a splendid song which he composed about the legend of the Grey Wethers. Sadly I can’t read music so I don’t know what the tune sounds like but the lyrics are brilliant and provide a great narrative to the tale – see above.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor