Here follows a delightful account of three men who visited Lydford Gorge in 1895 and who were being guided by a ‘local’ with an intimate knowledge of the terrain. Today it is easy to navigate yourself around Lydford Gorge and all that it has to offer but that has not always been the case, especially when there were no Health and Safety concerns. In the early days I had also been led by a ‘local’ with an intimate knowledge of the moor only to hear the famous words; “Well, it should be here somewhere, maybe a bit over in that direction, or was it further over the other side of that tor?” …

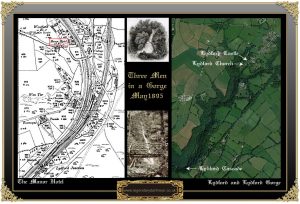

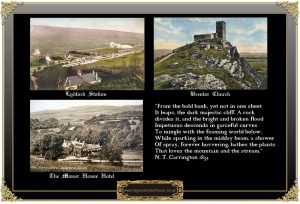

“We were only two in number when we joined the noon-day train at North Road, Plymouth, intent on visiting Lydford Gorge. But feeling ourselves somewhat deficient in knowledge of the Lydford geography, we had thoughtfully invited a friend to accompany us – one who by long residence in the very parish in which the Gorge is situated, would, we imagined, know all about its mysterious depths, and be able to guide us safely along the narrow paths and craggy ways of which we had heard so much. How our faith in this leader of men was justified – or – otherwise – will presently appear. He awaited us at Brentor Station, and we hailed him gladly, feeling an almost childlike confidence in his willingness, and ability to be – for the day at all events – our guide, philosopher, and friend. Together then we journey on to Lydford Station, where emerging from the railway carriage, we find ourselves in the midst of the moor. And truly no grander place could we desire than Dartmoor on this fine May day. Away to the left the moor stretches for miles, its broad grassy slopes reflecting sunshine and clouds in marvellous manner. Looking back the church crowned eminence of Brentor is seen standing boldly out in the clear atmosphere, and on the right of the station out of green fields rises one of the lesser tors, its cold granite crags jutting out from the grass and lichen around it.

A perfect day for the moor, the pure, invigorating, appetising atmosphere of which speedily induces us to bend our steps to the Manor Hotel, close at hand. For beautiful scenery alone will not satisfy hungry mortals of the ordinary kind. In and around the well-known rendezvous of sojourners upon the moor there are many visible signs of improvements effected by the new managers, who have evidently gone the right way to command success – by deserving it. Rooms have been added, with all the modern comforts and luxuries required these nowadays, even in moorland hotels; new and excellent furniture replaces the old; while outside the finishing touches are being put to the gardens and tennis ground, which our prophetic souls souls tell us are destined to be the scene, ere long, of many a flirtation and romance. At present, however, our interest is chiefly centred in the dining-room, where presently we are enabled to sample various products of Dartmoor, both animal and vegetable; and having concluded our repast we feel convinced that the stock of provisions kept in readiness at the Manor Hotel must perforce be of very considerable proportions. How otherwise could the keen appetite created by the moorland be satisfied?

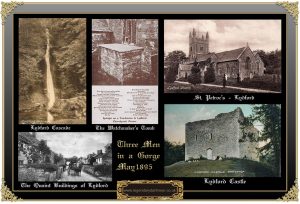

The full beauty of our surroundings appeals to us with even greater force when, after a brief, but satisfactory, sojourn to the moorland hostelry, we set out for the Gorge, making our way through the Manor grounds to the steep declivity which leads to the desired direction. On one side there is a typical Devonshire hedge, thick with verdure and gay spring flowers – primroses, anemones and violets, the latter abounding. Young ferns of palest green spring from the earth, watered by the tiny streams that seem to trickle from out of the rocky hedge and find their way along the roadside until lost in the thick growth of emerald-tinted moss. Small wonder that in such a place the flowers seem brighter and bigger than usual, and the blossom on the wild apple tree of sweeter scent and growth. On the other side the ground slopes steeply down to the valley beneath, a tangle of thick wood and undergrowth hiding the stream, which can be heard rushing merrily along. In a little while the bottom of the valley is reached, and we are alongside the rushing water which comes pouring down the from the Gorge some miles further up the valley, towards which we bend our steps. The famous Lydford Cascade is near at hand we know, and presently, with amazing suddenness, we come full upon it, in all its romantic beauty. Truly a wonderful sight it is as, standing by the side of the stream below, we look up and see this other stream, which from a height of more than a hundred feet above us, pours its torrent of white waters down the face of the black and gloomy rocks, between thickets of trees and leaves and ferns. April rains have been plentiful, and so the stream, that rises somewhere up on Black Down, is full, and the cascade more beautiful than it will be after the summer sun has parched the moor. Looking up at it we think of school days long ago, and Southey’s wonderful description of the falls of Londore, which, with its tantalising rhymes, has cost us many a difficulty. But Dartmoor too, has its poet, who, of this stream, has sung, telling with truth how:- (see Carrington’s lines below).

And now, having seen Lydford Cascade, our next purpose is to go up the narrow glen until the Gorge is reached. But this is easier said than done, for we are on the right banks of the stream, and the proper road for the Gorge lies, we are told on the opposite side, to reach which the ‘foaming world’ of waters must somehow be crossed. Rude stepping stones there are, it is true, but very far apart they seem, and the stream runs fast and deep between them. A kindly-hearted artist of the camera, who, with the enthusiasm of youth, is wading deep in the running waters, in order that he may obtain a favourable picture of the cascade, offers to carry us across, but the giant of our party – who weighs over fifteen stone – kindly, but firmly declines the proffered assistance. And we cannot doubt his wisdom in doing so. Thus, knowing that the Gorge undoubtedly lies somewhere up the valley, we decide not to cross the stream, but to follow the path on the right bank, and see if we cannot reach our goal in that way. Our native guide may have had his doubts as to the wisdom of our course, but he feared to risk disaster in mid-stream; and so we set forth on our exploration. Alas for our success or failure. We followed our path as long as we could, in spite of many hindrances, but at length it ceased, and in order to avoid retracing our steps we were compelled to follow the example of our photographic friend, and wade across to the other side. Then, had our native guide possessed the qualities we had fondly attributed to him, all would have been well. But truth compels me to state that he did not shine as a leader of men, and betrayed a woeful amount of ignorance as to his whereabouts, and this, notwithstanding that his foot, so to speak, was on his native heath – except when, as frequently happened, he and we slipped off a particularly steep and rocky ledge, “Keep by the side of the stream,” said our guide, “and we are bound to reach the Gorge.” We did as commanded, hoping for the best, but perspiring dreadfully.

Then, “struck by the splendour of sudden thought,” and forgetting his own advice he departed from the water-side and climbed boldly up a steep and narrow path. Where it led we knew not, but with wavering faith and still more wavering steps, we followed our guide, only to find, when at last we passed and looked around, that we had undoubtedly deserted from the way that led to the Gorge, and were now near the fields above the valley. Lovely, indeed, was the prospect from the height to which we had clambered, and our guide seemed particularly anxious that we should enjoy it to the full. All around us, above and beneath, the trees were budding into life, the pale green tints of larch and elm, contrasting beautifully with the darker masses around. Far down in the bed of the glen flowed the stream, its waters gleaming here and there between the trees until lost to sight in the depths of the valley, along which we had come. Somewhere up the valley, where the trees are thickest, and the steep wooded sides of the glen came close together was the Gorge – so at least our guide assured us. And doubtless it was so. But having clambered so far and long in the heat of the afternoon sun, which shone with unwanted warmth in the sheltered glen, we were not minded to test further the powers of our guide, and decided to postpone until another day our visit to the gorge proper. A short climb to higher ground, and we were not far beyond the grey pinnacles of the old church of St. Petroc at Lydford Churchtown. We follow the path across the sloping fields until the church is reached with the massive tower of the ancient castle adjoining. On this lovely May day, when the crumbling walls of the old castle, form a picturesque and beautiful ruin, it is hard to realise the horrors with which centuries ago Lydford Castle had been associated, until the sixteenth century it was officially characterised as “one of the most heinous, contagious and detestable places in the realm. According to an old poet: – To be therein one night its guest, T’were better to be stoned or pressed, Or hanged ‘ere you come hither.

Far more pleasing to see are the hallowed associations connected with the quaint and beautiful old church of St. Petroc – a church which something is recorded as far back as 1237. So much there is of interest concerning this little church of the largest parish in England, that we could willingly spend a considerable time within its walls. But time presses, and we can only stay a few minutes with Peter, the old parish clerk, while he points out various features of interest in the church he has so long served. This same Peter has had some experiences in his career, which he was not allowed to enter upon without a struggle, in the course of which an aspirant for the office of clerk once “tore” all the buttons of Peter’s ‘weskit’ – truly a lively beginning to the clerkship. As we leave the old church, Peter beckons us to follow him to a grave hard by the south porch. Here, resting on a box-like monument, which looks as if intended to keep a body safely underground, Peter recites with much gusto a quaint epitaph, the ancient lettering which can be faintly traced upon the large, flat slab. – see ‘The Watchmaker of Lydford‘.

And so, if we have not fully seen the Gorge from end to end, we have not failed for want of endeavour; and having viewed the famous Lydford Cascade in all its beauty, had a delightful scramble in one of the most delightful Devonshire glens, and spent a little while among the quaint buildings and records of the past, we come to the conclusion it will be well once again to seek the hospitable walls of the Manor. We do so, and are fortunate in finding an abundance of Devonshire cream and other delicacies with which to satisfy our healthy moorland hunger. After gazing awhile at the guest as calmly and steadily he devotes his best energies to the consumption of the good things so abundantly provided, we can scarcely help thinking after all the purpose of our scramble has be attained – we have seen a Gorge.” – The Western Evening Herald, May 10th, 1895.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor