In 1921 Eden Phillpotts published a book of Dartmoor short stories called ‘Told at the Plume’ by which he referred to the Plume of Feathers inn at Princetown. One of the stories in the book was simply titled – Rugglestone. The events in this tale revolve around the famous logan stone near Widecombe-in-the- Moor known as – ‘The Rugglestone’. There is one popular folklore tale about the rock but in this story he gives his own fictitious version. So if you would like to see what it’s all about simply read on.

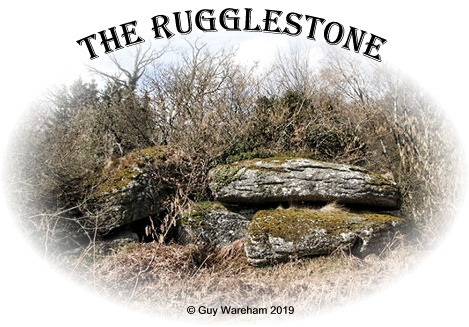

“A few of us was in ‘ The Plume of Feathers ‘ having a tell about things in general, when the talk drifted to the Rugglestone — a great mass of granite weighing a hundred tons and more — one of the most famous sights in Widecombe village without a doubt. It lies a quarter of a mile up the hill from the Inn — at the corner of one of Johnny Rowland’s fields and the amazing thing about it is that once on a time it was a logan rock; by which I mean the mass hung on another monster boulder, so clever as a door on a hinge, and it used to need but certain pressure to set it rocking. But that was in the old time before us, and none could move the logan now.

From the midst of the Rugglestone there lifted up a little rowan tree, which be there to this day, and it was one of the wonders of the stone how it could nourish a sapling five foot high and help it to grow and bear fruit in the proper season of the year. And the great stone itself was all covered over with moss and fungus — green and grey and black — a very remarkable freak of nature without a doubt — and thinking men often puzzled above a bit to know how the monster got there, and how it come to be set so careful on top of t’other. Then Johnny, from behind the bar, told us about the stone and a very strange tale what belonged to it.

“It fell out in my grandfather’s time,” he said, ” when things was different from what they are now and this house was newly built, because the place cried out for another inn for the labouring men from the farms this side the Vale.

“Folk took very kindly to the ‘Plume’ from the first, and the men from Blackslade and Tunhill and Chittleford and Venton and other outlying farms soon established a nice bit of custom. And not least among the regulars was a very quiet and kind-hearted man by the name of Christian Smerdon. He farmed Venton in those days — for ’twas long afore the Cobleighs went there — and he lived a widower without any family. You might have thought that to such a genial and child-loving soul, Providence would have sent a quiverful; but these things don’t happen according to human ideas of what be vittv, and Christian had neither chick nor child. In fact he was a very lonely man and so a lot of his warmth of heart ran to waste. A nervous and timorous spirit, though he was known to show good pluck with a drop of liquor in him, as you shall find.

“Well, he was here one night, and Jack Mogridge was here, and James Dunnybrig and his son, Valiant Dunnybrig, from Chittleford. No doubt a good few more had dropped in, for ’twas a Saturday, and thirsty weather just afore the harvest. And one other man must be mentioned also — him being a foreigner, by name of Lucky Knowles. At least, that was what he called himself; but I doubt not he had a dozen names and found it convenient to ring the changes upon ’em. A beetle-browed, night-hawk of a man — a gypsy to be plain; and him and his wife and two children lived in a caravan and went their rounds — now here, now there — selling wicker-work and spar-gads for thatching, and clothes-pegs and the like.

“A clever man with his hands and head both, and he might have stood higher in the world but for his disposition, which was rash and reckless. He didn’t neighbour kindly with house-dwellers, but liked to be free to roam; and he’d go and come as it pleased him. But he was pretty often in Widecombe; because our withy-beds tempted him a lot and he paid ready money for the withies and said that they were the best in the country.

“It all fell out most curiously I’m sure; and it showed two facts to the slowest mind; and one was that Christian Smerdon had a twist in him none among his generation ever guessed; and the other was that a gypsy can never be reckoned with. For a leopard sooner changes his spots than they Egyptians can alter their treacherous natures. T’was quite outside anything you might have expected to think that Knowles and Smerdon should have clashed; but clash they did and between ’em they made the story of the Rugglestone. Leastways the only story as I ever heard tell about it; but since it have doubtless laid there from the beginning of the world, no doubt many other strange things fell out before there was any clever people about to mark ’em or tell ’em again.

“The company was talking about the Rugglestone, just as we were to-night, and young Dunnybrig, he says to my grandfather: ‘ What be this tale about the Rugglestone, master ? ‘ And grandfather answers : ‘Just this, Valiant Dunnybrig. The great rock can still be shook in one way and only one. No power of man will move it more; but the truth holds good, I doubt not, though none put it into practice no more. ‘ And what be that ? ‘ asked young Valiant. ‘Why,’ said my grandfather, ‘you take the key of the church and go to Rugglestone at midnight and put the key under un as the church clock strikes, and then the stone will rock like a cradle ! For all his hundred tons he’ll move as easy as a feather. A dozen hosses and a hundred men couldn’t make him do it,’ says my grandfather; but the church key can. And that I steadfastly believe.’

“They laughed at him most of ’em — and Lucky Knowles loudest of all; but Christian Smerdon, he didn’t laugh, being a very serious-minded man with a great power of belief in signs and wonders.

“They argued about it and grandfather held to his tale most resolute, for he wasn’t a man to be shook by education; but only a few took his side. Then Smerdon spoke.

“‘Tis a pity that us of this generation don’t put it to the test,’ he said. ‘ After all, it ban’t beyond the power of thought for one of you chaps to go up over alone with the church key some night and see if the charm still holds good or be grown weak.”

“Gypsy Knowles laughed at that.

” ‘ Easy to talk ! ‘ he answered, ‘ but why for should you ask these clever men to do such a silly deed ? Because you haven’t got the pluck to do it yourself, Christian Smerdon.’

“At this attack, Christian fired up, as well he might. T’others laughed because he got hot, and that made Smerdon the more vexed. He’d had his two pints by then and was pot-valiant, or else perhaps he might have thought twice afore he spoke.”

“‘Like your impudence ! ‘ he said to Lucky. But I’d no more fear to visit the stone at midnight, than I’d fear to go there at noon. I’d snap my fingers at it!

” Lucky Knowles took him up quick at that.

‘ You think so,’ he answered; ‘ but you be out of reckoning there, for you haven’t got the courage to do it.’

” The crafty wretch wanted for Smerdon to fall in his trap, and fall he did. Twas a mystery to the men looking on, and not till three days later did the truth come out. Then they all gasped to see the Gypsy’s cunning.

‘ You say that I won’t take church key to the Rugglestone at midnight ? ‘ asks Smerdon.

“‘I do,’ answers Lucky. ‘ Tis your nature to be a coward. You can’t help it and ’tis no disgrace to you. But I declare that you wouldn’t go single-handed to the Rugglestone at dead of night ; and I’ll go further and bet you a golden sovereign you won’t.’

“‘Done! ‘ cries Smerdon, very excited; ‘Rowland can hold the stakes, and here’s my sovereign, and where’s yours?

” But Lucky was good for the money. He brought out twenty shilling and my grandfather counted it and put it in the till. A few friends of Smerdon, knowing his poor pluck, whispered to him to withdraw while there was yet time; but he’d got screwed up to such a fighting pitch by now that he vowed he’d see it through.

” ‘Tis beer be making you so brave,’ sneered Lucky Knowles, and Christian answered him:

” ‘ What then? If beer be making me brave now, no doubt ’twill make me brave again at the appointed time, so you’ll lose your sovereign and look a precious fool for your pains — beer or no beer ! ‘ he says.

” Which was one for Christian without a doubt.

” Two days later they fixed the night for the trial and then old Dunnybrig, as didn’t trust the gypsy a yard* asked him where he was going to be on that evening.

” ‘ You needn’t fear me,’ answers Knowles. ‘ I’m off to-morrow at sun-up and shall be twenty mile away when Smerdon here goes to the Rugglestone. I’ll drop in for my money a fortnight hence. And I expect the man to be fair and straight with me and confess in due time that he couldn’t do it. And I trust that none will help him or play me crooked behind my back’

“With that the gypsy took a tea-kettle of broth, as he’d bought from my grandfather for his missis, who was a bit ailing, and away he went to his caravan, in the corner of a watcr-meadow, under Venton nigh the withy-beds.

And he was as good as his word, for with morning he was gone and nought left to mark the place but chips of wood and bark of withy-bands, where he’d been at his basket work, and charred stones and a black patch on the earth, where he’d had his fire, and a litter of old boots, as he always seemed to leave behind him.

So there it stood and the eventful night come round and Christian borrowed the key of the church from old Mother Arnell, whose business it was to keep it for visitors. He drank till closing time and went home to Venton more than market merry. Indeed all his friends were a lot put about for him, because they thought he’d be very likely to break his neck getting up over the rough ground to Rugglestone in the dark — even if the beer held to him till midnight and lent him the needful courage for the task,

” My grandfather thought as highly of Christian Smerdon as any man, and so he lay awake that night anxious like, listening for twelve o’clock to strike and hoping that all was as it should be.

” Then, five or ten minutes after the bell had beat from the church tower and grandfather was dropping off, what should he hear but feet running fast ! A minute later somebody come to the door and Mr. Smerdon’s thin voice was lifted up in the darkness.

” ‘ Gaffer Rowland ! ‘ he shouted, ‘ for the Lord’s sake come down house and let me in ! Here’s a most amazing miracle have happened and surely to God no such thing ever fell out before !

My Grandfather was up like a cricket. At first he thought as Christian had met with foul play and Lucky Knowles had hid for him and took the key and made off to church with it to steal the alms box or some such devilish deed; but nothing like that had fallen out. And when grandfather went down and teened a candle and oped the door, there was two voices, if you please; for Christian was talking and a babby was screaming !

” Smerdon had a bundle in his arms and out of it was coming a little pipe, shrill as a bird.

” ‘ Guy Fawkes and holy angels ! ‘ cries out my grandfather. ‘ Whatever have ‘e got there ?

” ‘ A human babby ! ‘ answers back Christian. ‘ To the stone I went, brave as a regiment of soldiers, but scarce was I beside it when I heard a child hollering and shrieking like a sucking pig being killed. And my knees smote and my hair rose and my sweat poured, for I thought for sure ’twas a wishtness or some other kind of ghost. But then, waving my lantern afore I turned to fly, I seed a bundle right under my nose, and the homely look of it braced me up and calmed my terror. No doubt the Lord made me brave for His own good reasons. ‘Twas just this blanket laid on a bit of dry fern under the rock I found. And I saw that ’twas a child, and went to un and picked up the little creature and saved his life.’

” Meantime grandfather had opened the parcel and took a look.

‘ Tis the tiniest babby ever I seed/ he declared. ‘ A man-child and not much bigger than a Skye terrier. A fairy changeling so like as not; but his lungs be all right for certain. He ain’t been born a fortnight from the look of un and ’tis very clear he’s cruel hungry.’

Christian Smerdon was as much excited as if he’d found a gold mine.

‘Finding’s keeping in a case of this sort,’ he said. You bear me witness, Rowland, that I come upon the child quite friendless out in the open world, all alone under the Rugglestone at dead of night; and I defy and deny any mortal creature to take him away from me !’

” ‘ The Lord will take un away from you if you don’t bustle round and find somebody as understand babby’s food,’ said my grandfather. ‘ A tender bud like this can’t go very long without attention, so you’d better go oft and wake up some woman so soon as you can. He bant at all in our line and there’s no females here of a night since my darter married.’

” By good chance Christian had a great friend whose wife was a nursing mother at the time. She didn’t live above three mile off, and my grandfather fetched out his pony, and in ten minutes Smerdon was away galloping to Ponsworthy to wake up the people and get his new-found treasure a drink. No more afraid of the dark than you or me, I do assure ‘e.

“And the upshot was that he stuck to the child and adopted it and flouted all the rumours and warnings against such a dangerous step. For of course ’twas clear as light that Lucky Knowles, knowing how fond Christian was of childer, had fixed upon him as a father for his third. Like the cuckoo he was, and worked it very cunning so as his child should drop into Smerdon ‘s nest at Venton. And so it fell out, and no doubt the gypsy and his wife also were hid not twenty yard from the Rugglestone that night to see that all went well.

” The police was for hunting down Lucky and Mrs. Lucky so as their crime might be brought home ; but Christian assured ’em their trouble could be spared.

“I don’t know and I don’t care where the child came from, he declared, ‘but Providence have chose to send it to me, and ’tis a thing that I’d rather have than be lord of the manor; so I be going to cleave to un ; and for that matter the toad knows me already and wild hosses couldn’t drag him away from me.’

“The babby was named Christian Pancras Smerdon, after his foster parent and the church saint to Widecombe. And most people thought the saint ought to have come first. A very good, clever chap; and carried on the name in his turn, though the proper Smerdons of Bone Hill and Southways never would own him. He married a Coaker and prospered, but they be all gone, of course, years and years ago. The Smerdons was a great race and lie thick as grass in the churchyard to this day.

As for Lucky’ Knowles, such was the cool cheek of the man, that six months after Christian found the babby, his caravan turned up again by the withy-bed, as if nought had happened, and of course he dropped in to the ‘Plume’ to know if he’d won his bet. And when they told him about the child, and axed if he could throw any light upon such an adventure, he appeared to be very much astonished and declared, so solemn as need be, that ’twas all news to him. He was a lot more troubled at losing his bet.

“All the same they did say that Lucky’s wife went over to Venton one day, when Mr. Smerdon was to market, and waylaid the nursery maiden in Webburn Lane and had a good look at the child and told the girl that he was shaping for a very fine boy, and axed half a hundred questions, and gave a lot of advice about young Christian Pancras, as didn’t ought to have been any business of hers.””

Phillpotts, E. 1921. Told at the Plume. London: Hurst & Blackett Ltd.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor