“There is a miniature alpine bridge that crosses the Walkham at its junction with the Tavy, near the spot just named; this consists of a single plank, with a light piece of wood extended as a hand-rail to hold by in passing. In one part the plank is supported by a clutter of rocks beneath, as a Devonian would say in describing it. To stop on the middle of this plank and look around, will afford the greatest delight to the lover of the picturesque ; but let him beware his head does not turn giddy, for though he would have but a very few feet to fall, such is the tremendous force of the current in this place, he would be instantly whirled down like a snow-flake, should the waters be at all full, as they always are after recent rains or sudden heavy showers. A poor girl was lost off this bridge not long ago, in crossing it to go to church. A farmer, also, who had been carried down the stream, was found drowned; and many thought he had fallen, perhaps, into the river from this plank ; the railing is only on one side ; it is altogether very dangerous… Not afraid of falling, as the plank was quite dry, I stopped half way in crossing to enjoy the scene around me. Such was the roar of the water, for the stream was very full, that I could not hear a word Mr. Bray said, as he stood calling to me from the bank only a few paces distant. After looking for two or three minutes on the rocks, the rush, the foam, and the whirl of the river, I felt my head beginning to whirl too, so that I delayed not a moment to get off” as fast as I could from so dangerous a footing ; and I could very well understand how it might be that from time to time so many persons lose their self-possession by a similar affection of the head, and fall into the stream below, whence they are hurried on to meet death in the first deep pool into which they are borne. These bridges are called clams, and they arc never found any anywhere excepting across our rocky and mountain streams” – Elisa Bray, pp. 264-265.

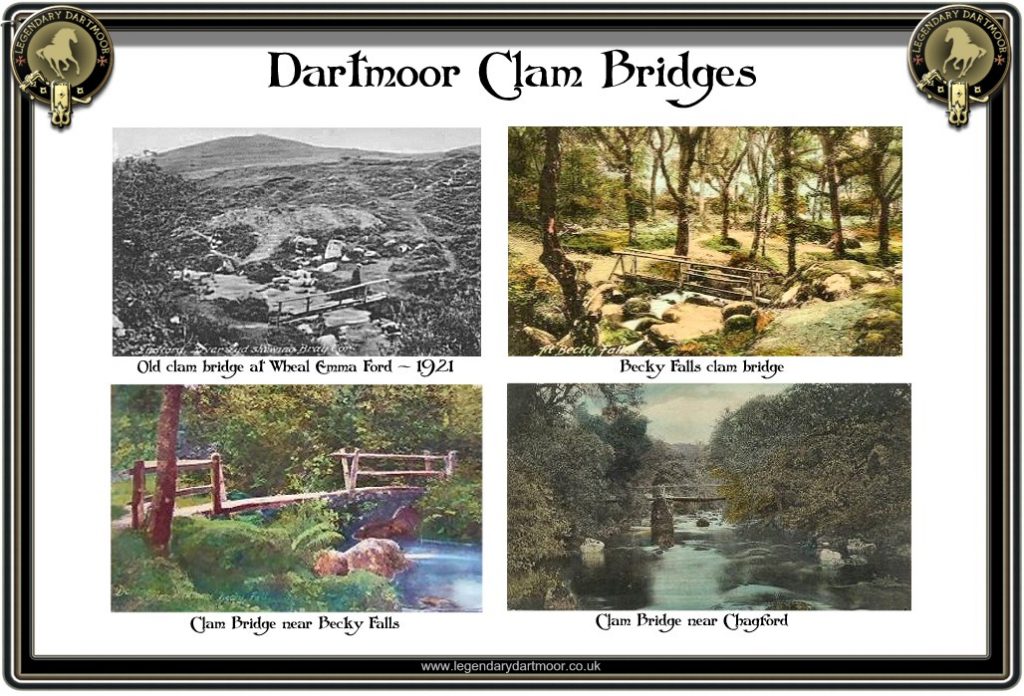

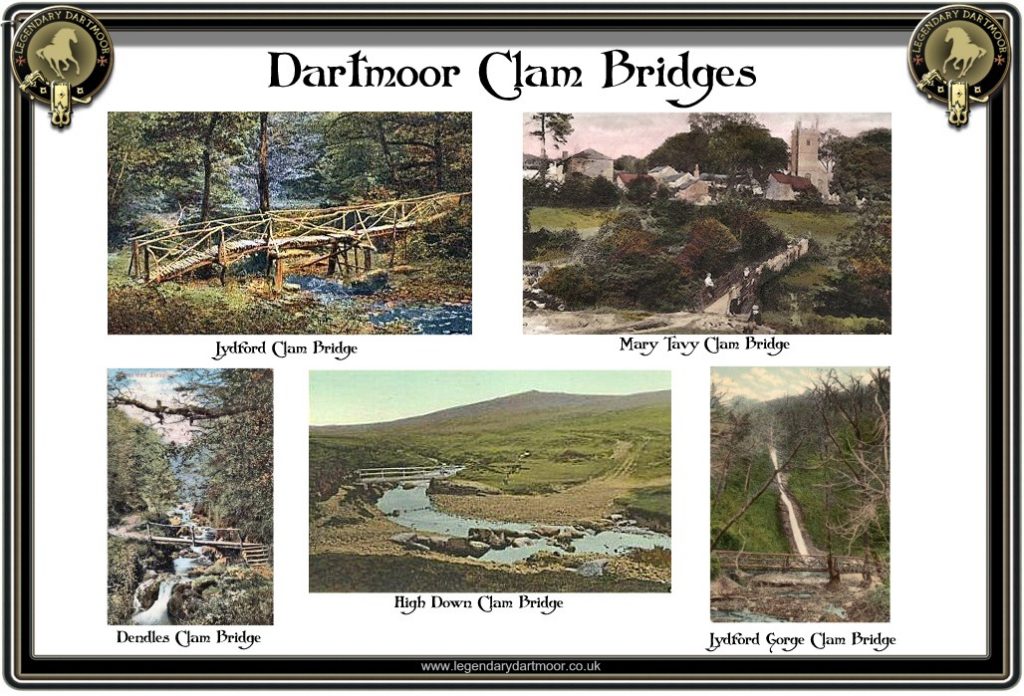

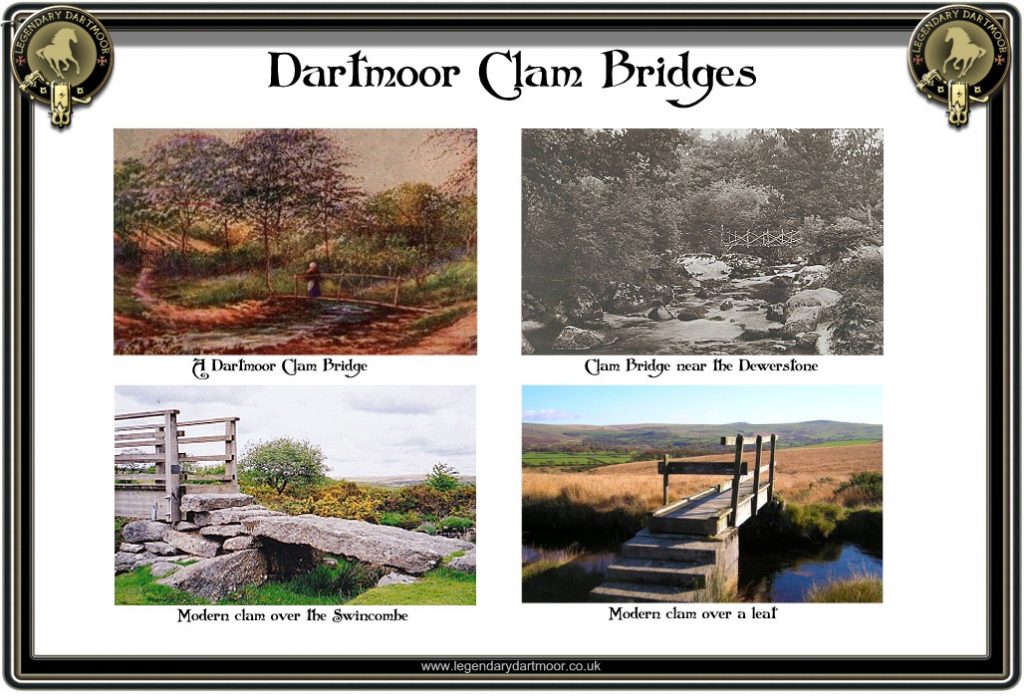

There were/are various means and ways of crossing the rivers and streams on Dartmoor. These are either fords, steps (AKA stepping stones), Clapper Bridges, conventional stone road bridges and clam bridges. Having already discussed steps and clappers here on Legendary Dartmoor (follow the links above), now it’s the turn of Clam Bridges. Clam bridges are best described as being footbridges that normally occurred/occur around watercourses which are at or near to settlements. Very rarely would there have been clam bridges on the higher moorland purely for the fact that any such wooden structure would soon rot away when exposed to the harsh elements. Due to the availability of granite on the high moors most of the river and stream crossings would have been stone clappers of one kind or another. In a similar light timber would have been the most ready available bridge building material in and around the towns and villages – hence clam bridges. The purpose of these clams would have been to allow access to and from the settlements for travellers on foot. Where they occurred in farmland it would allow the farmers to move around their various fields and enclosures.

There has been some debate as to the true Dartmoor definition of a clam bridge. William Crossing considered that they were; “a wooden footbridge; seldom seen on Dartmoor,” p.14. Eric Hemery simply defines them as a; “wooden footbridge.” p.30. Whereas Samuel Rowe has a slightly expanded suggestion when he stated; “Some of these (clapper bridges) are formed of a single stone, and would then probably come under the vernacular denomination clam, a term also frequently applied to a bridge formed of a plank or single tree, although we have noticed a distinction sometimes made, the wooden bridge being called a clapper, and a stone bridge a clam.” p.65. In one sense Rowe is correct in his definition insomuch as in other parts of Britain a clam bridge refers to a single stone slab crossing a watercourse. However, in Dartmoor terms as another author, Thomas suggests; “the name ‘clam’ is used in Devon and Cornwall to describe a bridge of timber…“. p.166. It is possible that the word ‘clam’ derives from the old Anglo-Saxon word ‘clamm‘ which means to grip or grasp and would allude to the fact that one needed to firmly grip the handrail when crossing one?

I think in Dartmoor terms we can accept that a clam bridge is one constructed of timber and consists of one or two spans. In the main the spans are constructed from tree trunks or slats/planks of wood along with hand rails, however just to throw a bit more confusion there have been instances of just a single plank known as ‘planks’ (as in Pearce’s Plank). Many writers consider that a single tree trunk thrown across a watercourse were the earliest examples of prehistoric bridges. As these structures are made of wood many of them have rotted away or been carried away by flash floods when the watercourses are in spate. In many cases the clams just survive as old place-names only which can be found in topographical writings, old field names or reports of early fox and otter hunt days. In some instances the ‘FB’ (foot bridge) symbol on Ordnance Survey maps may indicate the existence of a clam bridge at one time or another. As noted above clam bridges are rarely found on the open moor and therefore very few still exist as place-names. I have found; Clam Bridge (North Bovey), Fairy Clam (Swincombe), High Down Clam (River Lyd), Mary Tavy Clam (River Tavy) and Sherberton Clam (River Swincombe) and Swincombe Clam (River Swincombe). In the case of field names here are a few examples; Clam Close (Lower Cator), Clam Pit Piece (Cresslands), Clam Close (Higher Warmhill), Clam Park (Sanduck), Clam Marsh (Pitt Farm), and Clam Bottom (Newton Farm).

Clam Bridges have not completely disappeared from Dartmoor as more sturdy modern various have been erected such as the one at High Down Ford crossing the Lyd and another below Beardown Tors which spans the river Cowsic and Clam Bridge at Lustleigh (see below). Quite recently a single plank has appeared which spans the Devonport Leat just below Beardown tors, how long that will last is anybodies guess.

As Elias Bray related above some clam bridges were not always the safest forms of crossing a river or stream. In 1894 a miner from the Lady Bertha Mine was crossing the river Tavy on a plank and fell in. Despite a comrade dashing forward and catching him by his shoe it came off and the poor man was washed away and drowned. A similar case was reported of a young girl who fell from a clam bridge, again it spanned the river Tavy in 1897.

There has always been contention when a clam bridge needed repair and the argument normally centred around who was responsible for the costs. In 1947 the clam bridge at Lustleigh was in dire need of repair and as it was located near two parishes the cost were joint met by the Lustleigh and Manaton Parish Councils. In 2007 the Lustleigh Clam, more commonly known as simply the ‘Tree Trunk Bridge’ once again was a bone of contention. The Dartmoor National Park Authority that the 120 year old clam had become “unsafe” to use. After several meetings between the Lustleigh and Manaton Parish Councils the DNPA proposed building a completely new structure and remove the old one. This decision infuriated the locals who wanted the old bridge was of historical importance and should remain. Devon County Council the entered the affray and insisted that for Health and Safety reasons the old bridge should be fenced off. Today both the old clam and the new bridge sit side beside each other with a simple safety warning notice on the old one. In 1880 the clam bridge over the river Tavy near the Virtuous Lady mine was often used by fishermen got washed away. A Mr. German who held the fishing rights to the river along this stretch had received many complaints from those using the bridge. He therefore suggested to the Tamar and Plym Fishery Board that he would sell the old bridge for £1 and cut the timber for a new one on the condition that an annual rent of 6d a year was paid to the Earl of Devon. In 1891 there was another debate about who should meet the costs of replacing the Mary Tavy and Peter Tavy clam bridge. This controversy was with regards to whether a contribution made by the Devonshire County Council to the Tavistock Highway Board would mean they had part ownership of the new construction. In 1838 there was an interesting law case between the Duke of Bedford and Sir R. Lopez in 1838 which involved a clam bridge. Basically the argument was that Sir Lopez had trespassed on the Duke of Bedford’s land in order to dig prospecting pits and shafts and removed quantities of copper ore. In addition works at the nearby Virtuous Lady mine had extended under the river Tavy were providing a considerable amount of copper ore. Therefore one argument that was presented to the court was that as a clam bridge had been thrown over the river Tavy by the Duke’s mining agent this then placed ownership of the river bed (in which the copper ore was located) to the Duke and the path leading to it also. The counter argument was that as the clam was supported on each bank the planks of the bridge did not actually touch the ground and should not be considered as grounds for trespass. In the end the jury decided that there were grounds for trespass but the ownership of the river bed should be a joint one.

In the May of 1924 there was a dispute about the public right of way from Shaugh Bridge to the Dewerstone. The then owner Mr. Hill, clearly stated that he owned the land and although there was no public right of way he allowed visitors to use it. At one time there was a clam bridge which crossed the river Meavy which over time became unsafe and un-usable. Mr. Hill pointed out that his uncle, the previous owner had leased some land to a quarrying company and it was they that built the clam in order for the workmen to cross. It was when the quarry ceased to being worked that the clam was allowed to rot away. At a later date a tenant of Mr. Hill rebuilt another ‘rustic bridge’ in order for him to allow access to and from Shaugh Prior where he worked. This bridge was then removed at Mr. Hills request. Following the uproar Mr. Hill then stated that if anyone would like a bridge and were willing to pay for the construction themselves he would give his permission. It did not take long for a fund raising effort to take place in order to build a new clam bridge. On the 8th of July 1924 the new ‘rustic bridge’ was completed and officially opened. It was reported in the Western Morning News that; “The new bridge has a solid foundation on huge boulders conveniently placed on either side of the Meavy, and is wide enough for two persons to pass each other. There is a rail on either side, and trellis work as a further safeguard for youngsters.”

Other disputes would often arise with regards to plank bridges, especially when the ceremonies of ‘Beating the Bounds‘ took place. Many of the Dartmoor rivers have small islands in them and it was normal practice to lay a plank across the river in order to gain access. Each island belonged within the boundaries of a certain parish and was claimed by laying a plank to it. But in some cases whilst Beating The Bounds these planks would be removed and then replaced on the side of the island of the opposing parish thus in effect stealing it.

Elisa Bray, 1844, Legends & Superstitions & Sketches of Devonshire. London: John Murray.

Crossing, W. 1990, Crossing’s Guide to Dartmoor. Newton Abbot: Peninsula Press.

Hemery,E. 1983, High Dartmoor. London: Robert Hale.

Rowe, S. 1985, A Perambulation of Dartmoor. Exeter: Devon Books.

Thomas, D. L. B. 1977. Bridges on the Teign River – Transactions of the Devonshire Association, Vol. 129. Devonshire Press.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor