Just imagine, it’s the late 1800s and a month ago you had just been ordained as a Catholic priest. You are enjoying your breakfast when out of the blue you get a request from your Bishop to go to the infamous Dartmoor Prison to conduct the Sunday service. The only directions you are given is that there is a train leaving at ten o’clock for Tavistock and that the Governor’s groom will meet you and then drive you up to the prison. Baptism of fire or what? Here follows the priests’ account of his experience at Princetown:

“Just one hour after I received the mandate I was sweeping along the broad gauge of the Great Western Railway, the scene of so many terrible accidents; and so an hour’s ride brought me to Tavistock. There was my groom, trap and pony. No need of an introduction. I stepped up, and away we bowled through the pleasant Devonshire valleys. Presently we began a steep ascent on a narrow and hilly road. Gradually, the leafy trees, and the rich hedgeways, and the grassy slopes gave way to scarce and sparse vegetation. The gorse took the place of hawthorn, and the spruce and fir shot up their lances where a moment before we watched the leafy birch and the elm. Then, these northern shrubs disappeared, the road became rougher, and as we mounted and crossed a steeper hill, the grey and dreary levels of Dartmoor stretched to the horizon like a broken sea. The ground swelled and dipped and rolled away into the shadowy distance; and here and there were huge piles, as of boulders flung together by giants; and for the first of many times I was puzzled when I heard them called the Tors of Dartmoor. Yet against the greys and browns of the moor were here and there patches of a still greyer or more leaden hue; and my guide, in answer to my mute curiosity, volunteered the information, “gangs of convicts at work, sir.”

I afterwards learned that these gangs consisted of from thirty to forty convicts, guarded by four of five warders with loaded rifles; that they spread themselves out over the tiny grass farms of the moor, and rarely attempt to escape. It is only when the thick white fog comes down upon the moor that these poor creatures ever dream of freedom. And hence, the moment the fog appears to descend, they are ordered to close in and form a solid square with a warder at each corner, until the fog disperses or they are ordered home.

My guide chatted on during the remaining three or four miles; but somehow I could not get my mind away from that desolate picture drawn by the master, Dickens, in “Great Expectations;” for excepting the sea and the hulks, here was the exact picture of the convict life he drew – the marshland, the fogs with their drip, drip of silent rain, the grey convicts, the iron around the ankle, the haunted figures, the despair, the desolation, the agony.

With such thoughts as these we rattled up the one street of Princetown; and I entered the priest’s house, built under the grave and gloomy shadow of the greatest of England’s imperial prisons. A little thing will impress itself indelibly on the memory under new and exciting conditions; and my only recollections of that Saturday evening are that I was attended by a convict dressed in navy blue, but with England’s broad arrows stamped in red upon every square inch of his dress; and that I wrote my sermon for the morning with a pen dipped with iridium and with ink that was simply made by pouring water into a small bottle of dark purple glass. “You’ve got your liberty,” I said to my waiter. “Not for a few months yet, sir,” he replied. “But you are not in prison,” I said. “Oh! no,” he said, “men of my rank are sometimes allowed outside the prison walls to attend the officers.” “But are they not afraid you might escape,” I said with some surprise. “Very little danger of that,” he said smiling at my simplicity. “What should I gain? I shall be free in a few months. If I attempted to escape I should be shot or captured, and that would mean a life sentence. Then these few months are made pleasant enough by some such dispensations from prison rule as I enjoy just now; as all these things are stronger than iron bars…”

Next morning, eleven o’ clock saw me at the prison lodge, full of curiosity and anxiety. Here let me mention that I received unfailing courtesy from all the officials – from the Governor down to the humblest warder, and everything was done consistently with rule, to make my acquaintance with convict life as agreeable as possible. I received an enormous bunch of keys from the lodge porter, with the strictest injunctions that I should not part with them for a moment to any person. Then I was directed to a barrel gate, which I opened and closed, shooting the big bolts twice in each case. I crossed a yard, opened and closed another gate in like manner and found myself at the Catholic Chapel. A convict dressed like my friend of the last evening, was just passing in. He and another served mass. I entered the Sacristy, and proceeded to vest, a warder standing behind me, and my acolytes, one at each side in deepest silence. Now, it is hard to vest with several pounds weight of iron hanging around your person; so I carefully placed my keys on a table before me, only to find myself tapped on the shoulder and politely reminded, that the orders were, that under no circumstances whatsoever was I to lose hold of the keys, or part with them. They were a source of considerable distraction, I must say, during mass. My acolyte on the right spoke indistinctly. He had sustained an injury to his palate. He had been a barrister enjoying a large chamber practice. Unfortunately for himself, he had got into society, had become pecuniary embarrassed, made some mistakes with his cheque book, and was arrested at a ball. He was now completing his sentence of five years’ penal servitude, and looked forward, with what pleasurable anticipation we can imagine to his reunion with his wife and the child he had never seen. The wives and daughters of the officers now filed in, and paced up to the gallery or choir-loft to the left. Then came a pause. The tramping of men was heard in the distance, which, when it came nearer, was diversified with the sound of the clanking of chains: and about twenty convicts, dressed in hideous yellow, and chained from wrist to ankle passed rapidly into the chapel. These were desperate characters, who had made more than one attempt to escape.

And here whilst I was waiting, a curious thought flashed through my mind – a query for psychological experts, and those accustomed to see a correlation in everything. I couldn’t put my conundrum to my silent warder and acolytes so I put it here. Why is yellow the convict colour; both with nature and with man? Why is it the symbol of the outcast, the abandoned, and the dangerous? Nature clothes all its ugly weeds in yellow, and hardly gives us a descent flower. Don’t shout “the primroses and buttercups!” The former is is cream colour, the latter is not yellow, but has strong tinges of the red of gold. With the exception of special chrysanthemums and the sunflower, I know no respectable flower that is yellow; and all nature’s outcast children are dressed in that ugly tint. The it is the symbol of dreaded sickners in the quarantine vessel; and I have said it is the special convict brand.

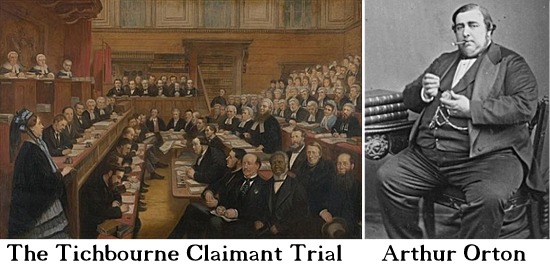

Whilst I am trying to solve this question, batch after batch of prisoners, accompanied by warders, have passed into the chapel, and as I take up the chalice, my warder whispers :- “Arthur Orton, the Claimant, is on your left under the gallery as you pass up, sir.”

(There was a famous Victorian court case lasting 188 days where Thomas Castro a butcher from Australia claimed himself to be Richard Tichbourne the lost heir to the vast Tichbourne estates. During his lengthy court hearing the jury decided that he was not Thomas Castro and definitely not Richard Tichbourne but was in fact Arthur Orton. He was found guilty of perjury and sentenced to fourteen years imprisonment and arrived at Dartmoor prison in the December of 1874. Due to the huge amount of media interest in his case he acquired the nickname of the ‘Tichbourne Claimant’ or simply ‘The Claimant’.)

Surely enough, there was the Claimant, a huge mass of humanity, leaning heavily on the bench and with his hand over his eyes. I saw him to more advantage afterwards: and my interest in him was rather reflected on his distinguished and eccentric counsel, whose two daughters are just now amongst the most celebrated Irish women in London: and whose long connection with my native town enables me to see this moment the roofs of his house property from my window.

I said the prayers and proceeded with Mass to the Gospel. Then passing from the altar to the Gospel side of the sanctuary I ascended the pulpit. This pulpit and the altar are the work of the Fenian prisoners at Portland. This white stone beneath my hand has been dug from what I had so often heard called “the blinding quarries of Portland.” Then I faced my audience. One dull, grey mass of humanity, with just the patient look upon them as you see on the faces of the blind. Some few held down their heads; as if ashamed to be seen by a stranger; but most of them looked steadily at the altar, and there was nothing in the least degree repulsive in their features. But the shock came from the fact that on every third seat and close by the wall on either side was a raised bench, like a piano stool, and there was a warder, holding what I thought was, and what must have been a loaded revolver, and looking away from the altar steadily and threateningly on the prisoners. there was something unspeakably painful in this exhibition of force in such a peaceful place; and it jarred terribly on my nerves, but I dare say it was necessary.

As I proceeded with my sermon two things disconcerted me. The only remarkable face I could see was that of a prisoner who sat third from the wall on the front bench beneath the pulpit. It was the face of an old man – a death’s head covered with parchment and surmounted with stiff bristles of white hair. He never lifted his eyes from my face whilst I was speaking, and his face underwent a series of violent contortions which it was painful to witness. My first impression was that he was trying deliberately to put me out. And to this day I am not quite sure whether that was a rash judgement or whether he was merely suffering from some facial contortions. Then, at the close of the sermon, instancing how little the saints thought of the pleasures or pains of life, I quoted the reports made to the emperor by his emissaries, who were delegated to arrest St. John: and the saints lofty disregard for the punishments of men. But when I quoted the words of the emperor: “I shall put him in prison,” and then the reply: “He will consider his prison a paradise, where he can safely devote his time to prayer and praise,” it was not exactly an English guffaw, but a very well-bred titter that ran from end to end of my congregation. I then saw how maladroit I had been, and hastily developing the conclusion, I ascended from the pulpit. The music of the Mass was rendered by an excellent choir, the leading voice in which there was a fine tenor belonging to a Liverpool bank clerk who had made some mistake in his accounts; the singers, all prisoners, were accompanied on the harmonium by the daughter of the Protestant rector of the parish…

“There’s a sick prisoner would like to see your reverence,” woke me from my reverie in the sacristy, and I followed my warder along the dreary corridor into a narrower and darker one, lined on either side by cells built of corrugated iron. A sudden shooting of bolts, and I stood looking in a cell so utterly dark that it was only after a considerable time I could discern a faint gleam of light from the left-hand corner: and after a long interval I could make out a dark form on the floor of the cell. It was a poor Irish prisoner, named Sullivan, who persistently broke the laws of the prison, and as a result had been so treated that he had lost his reason, and now lay in a straight jacket in this dismal cell. I knelt down and bent over him, not expecting that he would recognise me. But, with extraordinary instinct by which they say an Irishman knows a priest anywhere, and under any disguise or darkness the poor fellow sobbed out and cried, and whispered: “I know you are a priest.” I said all that could be said under the circumstances perhaps, the most miserable that the human mind has yet conceived; and then was let out into light and air once more by my warder. Let me add that the latter, himself an Irishman, had nothing but terms of supremest pity for this poor boy, and terms of indignation, too strong to be related here, for the official who drove him by harshners into this dungeon. “They’re too high spirited, your reverence,” said he, “for such a place as this – these poor Irish boys. And then they’re crushed.” As we passed along the corridor, the door of the infirmary was open. I looked up along its row of beds, and saw a prisoner dressed and standing by a pillar. “That’s one of the Fenian prisoners,” whispered my guide. “Could I speak to him?” I said excitedly. “I’m afraid not,” he said, “he hasn’t asked for you.” “It’s an awful thing to be on guard there at night,” continued the warder. “You don’t mind it in the beginning of the night, when they all sleep soundly; but when they turn in their sleep, and you hear the chains rattling under the bedclothes, and some poor fellow starts up and looks around him, wondering where he is, and perhaps dreaming he was at home, and then sinks back with a sob and cry, I often wished I was a hundred miles from here. But,” he added, “you mustn’t think they are badly treated here on the whole. There is not a prisoner within these walls, who would not prefer five years penal servitude to two years imprisonment in a county jail, the reason is that they are better fed, better looked after in general in these prisons. Why,” he continued, “if a gang were out on the moor, and a shower came on and they got wet, the doctor would compel every man of them to change the moment they came in for fear they’d catch cold.” – a proceeding which my friend, not through unkindness, evidently regarded as a most superfluous piece of politeness.

After dinner, the same warder to whom I had taken a decided fancy, walked with me two or three miles to the east along the course of a mill leat that ran towards the prison. It was a fine summer evening: yet I imagined it was cold and dark out here away from civilisation. And yet it was the very spot which an English King chose for the scene of unspeakable orgies; for here to our right is a square mansion, now in ruins, where, not content with the Babylonian festivities of London; our good monarch would retire for a time to be farther away from the gaze and criticism of his subjects (allegedly Tor Royal and King George IV). “He ought have been in Malleray,” said my guide. “You don’t mean the king?” said I, with surprise. “Oh no, your reverence,” said the warder, “but that poor fellow who served your mass this morning.” “You don’t mean the barrister,” said I. “No, but the other prisoner with delicate eyes. He’s almost a saint!” “Then what brought him here?” I could not help asking. “Ah,” replied he, “many an innocent man is brought here. And many a prisoner is here for what you call a venial sin. But the law is hard, especially if a man is detected a second time. But, Lord bless your reverence,” he said with a laugh, “they like to come here. As sure as I take down a discharged prisoner to the train, so surely will I take him up again in a month or two. ‘We’ll work if we can get it’ they say ‘but we won’t starve and we won’t go to the Union Workhouse.” “Do you know,” said I, “that remark of yours about Malleray suggests a comparison that was made by a great novelist, perhaps you have heard of him – Victor Hugo. He does not see much difference, so far as hardship is concerned between monks and prisoners. But I want to ask you two questions. What is the hardest part of the prisoners lot here?” “I think,” said the warder musingly, “that the hardest thing at Dartmoor is that you cannot choose your company. As the prisoners marched out of the chapel today, each man had to take as his comrade the next that he met. In this way a gentleman may have for his companion a burglar or worse; and you can imagine what that is. But, curiously enough professional criminals prefer life here to life outside, at least in this way. As ticket of leave men, and wearing the grey frieze we give them when leaving, they fail to get work, as you can imagine. They will not go to the Union Workhouse. Then they will commit some small theft and come back here generally with an increased sentence.” “There is no remedy, then,” said I, “for crime.” “None,” said he, “until the world become s charitable.”

Next morning, I stood at nine o’clock near the governor’s house. We were to drive to Tavistock. It was a glorious morning, even here. The very granite of the prison walls was sparkling in a thousand lights in the warm summer sun. But from the very quarry, whence the granite was taken, I saw cartload after cartload of blocks emerging, drawn, alas! by human hands and shoulders braced with stout ropes to their burden. A man stood near me, clad in grey frieze. He was a ticket of leave man, just free from prison, and going to face a bitter world again. His face was very pale; and he looked curiously and almost, one would say, with regret at the yoked prisoners. “Get up,” shouted the Governor’s groom. He started, and in his confusion, took the Governor’s seat. With a an oath, he was ordered to descend and clambered up behind with a shames face. We drove rapidly into Tavistock; and after a word with the governor, my prisoner and I were left alone on the railway platform. He looked dazed, and broken-spirited. In a few minutes the rumbling of the approaching train was heard. He started and grew paler. And when, with a shriek and a thunder of the huge wheels, the locomotive swept into the station; he fell against one of the metal pillars in a swoon. Civilisation was too much for him!

I have seen since I wrote the above, that amongst medical experts, yellow is supposed to have a depressing effect on those who are mentally affected, and blue an exhilarating effect.”

The Derry Journal, March 12th, 1894.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor