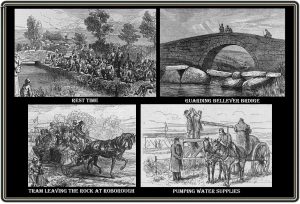

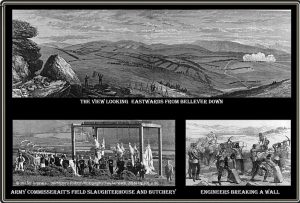

It is a well known fact that since 1873 various parts of Dartmoor have been used for military training. Today the areas on which this can take place are clearly defined but that was not always the case. In the August of 1873 some 9,000 soldiers took part in two weeks of manoeuvres with the main camp being on Ringmoor Down. The exercises were carried out over a wide area of southern Dartmoor, from Eylesborough to Roborough Down to Tavistock and Princetown. It was commented at the time how the landscape provided; “steep hills, rugged tors, sloping valleys, bogs (with the appearance of which every military man should be acquainted and thus avoid what would otherwise be a dangerous enemy), plains dotted with huge boulders, thick hedges, rapid streams, bad roads, copses etc., and what is as important, good level ground for division, brigade and regimental drills.” There can be no question that Dartmoor more than adequately provides all of those landscape features but there are also other components it also provides – rain. fog, and wind. No matter how careful the planning for such a huge event the only thing that can’t be reckoned with is the weather and on this occasion Dartmoor well and truly put a spanner in the works. A local newspaper report from the first day of the manoeuvres read: “The accounts we received up to Saturday presented a picture of camp life more lively than agreeable. The effects of the rain of Friday was enough to disgust the most seasonable veteran,and a correspondent describes the camp, with its long rows of tents, as like so many dejected mushrooms, while its ranks of miserable dispirited picketed horses, its utter absence of any sign of animation, make it from every point of view a place to be avoided. But a camp on Dartmoor, under rainy weather, superadds other depressing influences. The wet attacks the soldier both from above and below. There is no dodging it. Water last week lay in patches several inches deep, collecting in hollows, until it found vent through the natural surface channels, meanwhile soaking into the peaty substratum until the soil became thoroughly saturated.” A much more detailed account of the manoeuvres read:

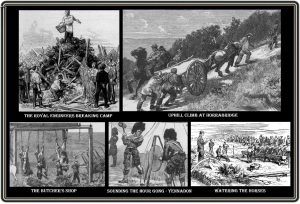

“The weather at Dartmoor has not been altogether favourable for the manoeuvres of the army corps. Soaking rain, such as is not seen in any other county of England, has made the ground of about the consistency of thick gruel, and when the rain has ceased it has often been succeeded by an impenetrable fog, making any attempt at the management of troops little better than guess work. There have, however, been occasional spells of clear weather, during which the men have been no means idle. There have been several engagements during the week in which both divisions have been employed, and the work done is generally spoken of as credible to all concerned. The management of the Control Department, which was at first thought to be the weak point, is said to be excellent. The base depot is at Plymouth, and there are a series of depots all the way up to the most distant camp. These depots do not draw supplies direct from Plymouth, but depend upon each other in the order of their distance from the base, so that in the event of a retreat the army would not be obliged to abandon large quantities of stores collected close to the front, but would on the contrary, fall back on a succession of well provisioned depots.

On Tuesday, as an spectator fell from his horse in consequence of an attack of apoplexy, and tumbled over the rocks being so injured that he died. During the manoeuvres some of the ammunition waggons were lost in the mist, and one whole regiment was marching up to Bellever tor, right away from its destination, when it was fortunately met by a civilian who happened to carry a pocket compass. On Wednesday the weather became so bad in the neighbourhood of Princetown that General Staveley abandoned the scheme of operations for the week, and sent the men back to Yennadon as fast as the defective means of transport would permit. It is not yet certain what day the Prince of Wales will visit the camp; but he is to be present at the ‘march past’ on the 21st.

The incident of the patrol is, of course, one of nightly occurrence. The camp is closed at a certain hour, after which every good soldier is either on guard or asleep within his tent. The patrol’s stern demand, “Any soldiers in here?” is, indeed, a terror to the truant soldier, who may have stayed too long over his pint and pipe in the tap room of the ‘Red Lion’, for he knows that absence without leave is one of the most heinous offences he can be guilty of.”

“Certainly camp life is apt to knock the squeamishness out of one. Every company has to furnish every day; two to fetch rations, two for wood, two for water, two to help the cook, two for picket to keep order in the camp, two for pioneers to do spade work and act as scavengers, and in addition has to furnish the guard in its turn. As our companies were weak, every private had to take a turn at one fatigue or the other about every two days, and in addition to this there was the tent to be tidied, rifle and bayonet to be cleaned – an endless task in wet weather, mess tin to be scoured, and boots and uniform to be cleaned, so that the ordinary camp duties took up no small amount of time. The great inconvenience was that most of this work was more or less dirty, and the opportunities of washing were small; one’s only chance was to take a bucket and trudge to the nearest brook, which might be a mile off. One had not always the time for this, and on such occasion one’s toilet was as limited as the ‘three stamps and damn’ of the privateer’s man. My hands were generally of a rich sepia with peaty soil, boot dubbing and oil, and I don’t expect my nails to be very respectable for another fortnight. However, cleanliness is an acquired instinct and the natural dirty savage soon crops out in most of us. The dirt was, however, not more external, as out cookery was highly primitive, and I am afraid not very cleanly. Certainly during the fortnight we all of us must have made large inroads into the peck of dirt which tradition says it is the fate of all sons of Adam to devour during their lives. To a person of delicate stomach it would not be pleasant to go on rations fatigue and see carcasses of sheep with the life barely out of them, loaves, and groceries chucked pell-mall into a dirty service waggon, with a dirty-booted, dirty-handed individual standing in the midst endeavouring to keep order in the chaos. Neither did I suppose till I tried it that I could slice up great gory joints of meat for the camp kettle, and afterwards devour the proceeds of my scullion’s work with the utmost relish…

But it is not only the men of one’s own corps that one comes in contact with. I saw a good deal of the regulars, and come to the conclusion that the British soldier is a grossly maligned creature. Of course, there are a good many black sheep, and sobriety might be more extensively cultivated; but still the better sort of privates and non-commissioned officers are men whom it is a pleasure to mix with.” The Newcastle Journal, Friday 29th August, 1873.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor