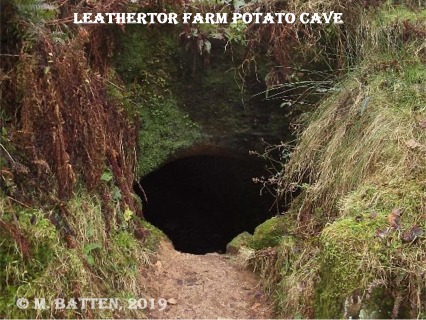

There are numerous caves and caches on Dartmoor but probably the most iconic are the potato caves. The majority of these can be found in the southern moorland parishes of Sheepstor and Walkhampton. But what was their purpose? Quite simply they were used to store root crops where they would be protected from winter frosts and daylight. Over time these features have been variously known as; caves, stills, hulls and voogas. On Dartmoor their construction simply involved digging a short tunnel into a hillside comprising of growan (decomposed granite forming a soft, sandy gravel). The size of the ‘caves’ varied with lengths of between 6 and 12 metres. Their heights range between 1.1 and 2.1 metres with widths between 0.9 and 1.8 metres. In most cases the caves were located near to the house hence giving easy access. Heritage Gateway gives the following description of the potato cave at Leathertor Farm; “Dug horizontally into the natural ground, about 2.6 metres back from the lane. The entrance is about 1.1 metres high increasing to about 2.0 metres inside. The cave extends back 8.6 metres. The entrance was fitted with a small gateway with short granite posts and a low hedge or bank about 2.0 metres thick.” The most important feature of a potato cave is that water should be prevented from getting inside, if it did then the crop would be ruined. As noted above in most cases it would be potatoes, turnips, and mangels that would be stored in these caves. One has to be a bit cautious when identifying potato caves because in some cases such caves were dug to extract the grown for use in a mortar mix whilst others were used to store tools etc.

One would have thought that potato caves would never feature in historic court and assize sessions but you would be wrong. Whether out of desperation or sheer laziness there are numerous reports of folk appearing at such events charged with stealing from the caves. One of the earliest I have come across was from 1849 when one George Clampitt was set for trial for stealing potatoes from George Hagget at Chagford. What is quite amusing is that in many such cases the culprits were found by following their boot tracks left in the mud around the caves. In 1854 William Greep and George Askell were charged with stealing potatoes from Robert Sercombe at Wisdome Farm near Cornwood. On visiting the scene of the crime PC Froude retraced a set of boot prints to Greeps House. He then continued to follow the trail which led him to a hedgerow ditch in which he found 65 pounds of potatoes. On examining the soles of Greeps boots the policeman noticed that several of the hob nails had been removed. Creep’s explanation was that he worked in a nearby quarry and it was there that they came out. A simple piece of detective work deduced that if they had still been in-situ then they perfectly matched the prints leading from the cave. The PC then called on Askell and asked to see his boots which miraculously had just been repaired. On removing the new sole it became evident that once again the number of hob nails matched the tracks previously found. The garden where Askell lived was searched and low and behold another sixty pounds of potatoes was found buried under some cabbages. Both men were found guilty and sentenced with Greep getting four months hard labour and Askell six months hard labour. This is but one of many such reports that appeared in local Dartmoor newspapers. It was not unheard of to use potato caves for hiding illicit stashed of alcohol or stills along with secreting poached game.

The other method of storing potatoes on the moor was in clamps. These were literally pits dug into the ground and then lined with straw or rushes filled with the crop and then covered with earth. Emptying a potato clamp was never a joyous occasion especially if water had seeped in. Here are the experiences of a Land Army girl; “Picture yourself a field of mud in the latter days of February. The snow had mostly thawed and left the ground a morass of heavy saturation; the frost had gone, but the mud had come, and a moist but bitter wind was blowing from the west. Picture, then, a steep hill-side of mud, sodden and uneven – for the land, dug last autumn when the crop was harvested, had lain untilled the winter through. The dull expanse is broken only here and there by long sausage-shaped mounds of earth – or caves, in which lies hidden the treasure we are out to seek.

The group at the cave is not unpicturesque, in a rather squalid and gypsy-like way. Most conspicuous first stands a big rough tripod, from which are hung the weights. Spread about are bundles of muddy bags and two or three large baskets showing signs of the season’s wear. Master’s homely figure, his extensive waist encircled by a sack tied round with cord, is seen bending over the pit with a curved and perforated shovel, attempting to ‘shooell’ up such potatoes as are fit. Jimmy (another Land Army girl) in muddy boots and leggings, sou’wester and oilskin coat, also with a torn and dirty sack about her like an apron, is rolling back the sodden rushes that lie like thatch upon the heap. Alternately, as the baskets are filled, we lift them onto the weights and fill up the bags – eight score pounds in each.

The theory is beautiful; and farmers will boast that they can pick up a truck-load before dinner time. But on a Dartmoor farm – or, at any rate, at our particular farm – theories we found seldom fitted in with practice. For alas! the rooks or rabbits had been at the caves, the snow had got through, and the ‘tatties’ were wet, mucky, rotten, and altogether depressing. Instead of shovelling them steadily into the baskets, shaking out the dry soil from among them, needs must we go upon our knees in the mud and with frozen fingers pick the up by hand, sorting out the good ones, and – ugh! the bad ones! Does anyone known the smell of a really rotten potato, and the revolting squish of yellow, evil-smelling custard that one’s fingers slide into? I think the combination of mud and a stooping posture, cold wet fingers and rotten potatoes, is one that might be calculated to make one – well, depressed.

But the day goes on; we stop for an hour at dinnertime and get comfortably warm by the kitchen fire – only to emerge once more into the bitter blast. The wind, though westerly, was as cold as any from the north, and howled in belching gusts up the slope of the hill, tossing bags and overcoats about, impeded by nothing in its passage from the snow-capped moor till it reached our exposed, defenceless little group in the midst of the open field.

With a spade, first the sodden earth must be scraped off the caves; then the rushes, wet and sticky, rolled back from among the potatoes; and then the potatoes sorted and picked. Except when shovelling, which we did in turns, there was not enough exertion in the work to warm a hen; and when kneeling on a mud-caked bag and fumbling among mucky tubers, there was nothing for it but to hump one’s shoulders and endure.

One after another the baskets got filled, and forty pounds or so at a time we lifted onto the weights, and lifted again, shaking their burdens into the bags – in a sufficiently severe test on the arms when continued for some eight hours or so during the day. “

As with caves the clamps were also vulnerable to theft by people looking for a free meal or to make a fast buck.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor