There are numerous reports of daring escapes from Dartmoor Prison over the centuries that appeared in newspaper reports and related books. Some were successful others failed miserably but the majority of these are told from the point of view of the captors and not the escaped convict. But in 1891 the Bideford Weekly Gazette printed an article relating the supposed experiences of one escapee from Dartmoor prison in his own words. Clearly if true the names and some locations have been changed for the purpose of animinity.

” I was tried for a crime I never committed (my readers will smile, but it is true, nevertheless), found guilty, and sentenced to seven years penal servitude to Dartmoor, and there, by degrees, became as comfortable as possible to one suffering from a strong feeling of injustice, separated from hi family and disgraced before the world.

In saying that I was comfortable, I mean that by good conduct I obtained many little indulgences; my work was comparatively light, and rewards in money were placed to my credit, in order that when discharged I should have something wherewith to start afresh. Moreover, so satisfactory was my behaviour considered, that successive deductions, amounting at the time of the following occurrences to fifteen months, were made from the whole period of my sentence.

Well, it happened that when I had less than a year to serve, I was one day doing some carpenter’s work in connection with a building we were erecting. I saw a party of visitors coming in my direction, and turned my back, as I always did when strangers came near me. I knew that even if former acquaintances of mine did visit the prison, the yellowish-grey jacket, knickerbockers, and triangular cap were a good disguise, apart from my shaven sallow face, yet I was always weak enough to get out of the way.

On this occasion I saw, without raising my head from my work, that someone stopped near me; then I heard a short, whispered conversation between the warder and this someone, and presently, as my guardian retired I heard; “Don’t look round, Newcombe, Jack, old boy, listen but don’t look.” In spite of myself, I did so, and a single glance showed me Ned Chambers, an old chum. The next moment I was busy with my plane, and Ned seemed to be intently examining the grain of a piece of timber. “Do you remember the hole near Cranmere where we drew the badger?” Ned went on. “Any time you go there you will find clothes and money. Don’t be in too great a hurry, watch for a good opportunity.” That was all he said, and he went away, leaving me trembling so much, I was obliged to cease work for a while. Up to that time I had never dreamt of escape, perhaps because of the difficulty; now I could think of nothing else. The year I had yet to serve seemed an eternity; every duty became repulsive; my food hardly touched; and, being wrapped up in a single thought, I became the most unsociable of beings. Some of my gaolers and fellow prisoners jeered at me, but ‘off his head’ was the general verdict, and I seized that as a reason fro requesting outdoor work, which would give me the opportunity of carrying out my plan. Accordingly I was sent to the fields, and a week or more passed quietly.

I might as well explain here that some hundreds of acres round the gaol have, from time to time, been reclaimed by the labour of prisoners, and the establishment works its own farm, raising crops, and so on.

Well, we were arranged in gangs, fourteen in each, in order to hoe up potatoes, and all went on in the usual way until, perhaps, four in the afternoon, when a fog came on. Dartmoor fogs are something of an experience. Sometimes, in perfectly calm weather, they descend without the slightest warning, and in ten seconds you can’t see beyond your nose; sometimes you notice a little haze in the quarter of the wind, which comes towards you in clouds that roll and curl playfully, gradually increasing in size and density, and in less time than it takes to read this, wrap you in a damp cold mist.

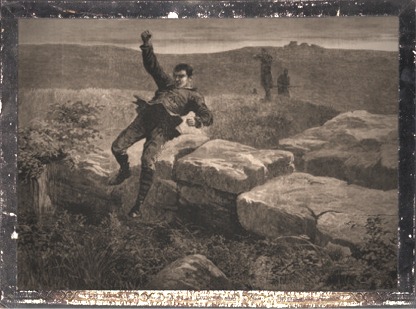

This fog was of the latter kind, and when it was seen above the next hill, the customary precautions were taken. The cordon of guards, usually stationed a couple of hundred yards away, closed round us, and each gang was ordered to fall in. How my heart beat! While taking my place in the file, I glanced round, seeking the most open direction and while the guards of my gang were engaged with a laggard, I sprang into the mist. The shots followed me in quick succession, but I prepared for them by swerving from my course, and was not hurt. The side nearest to the prison was naturally the least guarded, and towards it I ran, hearing on all sides loud shouts and hurried orders.

Having already decided on my course, after making a short detour, I crossed the Tavistock road, which already rang with the tramp of horses. I well knew the meaning of that. The highways would soon be scoured by mounted guards, the farmers and their men would be roused, and the country would presently be alive with people eager to earn the five pounds payed for the capture of an escaped prisoner.

I am not a native of Devonshire, but Ned Chambers and myself had during holidays of three or four years fished the rivers of the vicinity, and I knew almost every foot of Dartmoor. My plan was to go nearly due north, across the wildest and most treacherous part of the moor, where, for the seventeen miles that separated me from Okehampton, I should pass only one house, or at the most two.

Keeping, then, to the left of the rod, I made for Baredown, and upon reaching the Tors, paused for breath, and listened. Cries of men and the barking of dogs came from every direction, but all distant, ponies and bullocks, alarmed by the unwanted noise, rushed past be to the valley, and the sound of heavy hoofs, like those of mounted horses came from the heights to my right. I descended towards the bed of the Dart, and here a new danger met me.

Hearing a noise near, I crouched down and listened, and presently something approached me slowly, seeming in the mist to be of gigantic proportions. Then there was a sniffing, then an angry bellow, and the bull, for such it was, retreated for a few steps, and charged. The deep bed of the watercourse was beside me, and I sprang into it, and crept under a large boulder that crossed it. Here my assailant could not touch me and I cowered there while he passed round and round. Soon other steps approached, and the bull, with a fierce roar, set off at a gallop, and I believe turned the tables on one of my pursuers.

By this time I was in complete darkness, and I pursued my way. What a night it was. Stumbling over boulders, slipping into bogholes, bruised, bleeding and exhausted – such was my condition. Pushing my way – feeling it, I might say – through a cold, clammy fog, now a sound to the left making me dart to the right, now on the right, driving me to the left, my limbs trembling, and my heart almost standing still. After what appeared to me centuries, I reached Cut Hill, eight miles from my starting place; and here I made a long halt. All sounds of pursuit were ended, and I should be able to continue my flight with fewer precautions. I was dreadfully tired, and hungry as a hunter, for I had eaten but little of the bread and thin soup that constituted my dinner. On, however, I must go, as it was necessary to be out of reach before morning, when the chase would commence.

Soon after midnight, as far as I could judge, the fog disappeared and the stars shone out, and with their help I got to the spot mentioned by chambers.

One day when rambling about with our terriers, we tracked a badger to his hole, and after a lot of burrowing, the dog drew and killed him. I was now standing beside the sloping bank from which we had watched the battle. The hole was stopped by a large stone, which I removed, and upon eagerly thrusting my arm in I found a knapsack. A hasty examination showed me a complete outfit, even to a spare shirt, collars, and false whiskers; and in one pocket was a purse, containing a note, with some gold and silver.

In the hope that I should supposed to be drowned in the bog, after changing my boots I threaded my way carefully into the quaking morass, dropping first one boot and then another, and, after preceding about a hundred yards, hid my coat and vest where I knew they would be found. I could at present spare no more, as I wished to keep the other clothes decent. So far, every step could be traced by my footprints and before me was a pool of inky blackness, which I had no wish to sound.

After feeling about for a few minutes, I got a narrow line of hard soil that led to higher ground, and, with knapsack strapped across my shoulder, I turned off sharply to the right, so as to reach the Moretonhampstead Road. The grey dawn was appearing as I entered on that highway a mile beyond Merripit Hill and after a good wash in the stream I changed my clothes. My prison garments I made a bundle of and hid under a stone, and then I surveyed myself. I whistled joyously, the change was so marvellous.

Every hamlet around Dartmoor would, in the morning know of my escape, and after much deliberation I decided that the safest course would be to hark back through Princetown, where no one would expect to see me. First, however I walked on for another hour, and the, abruptly turning, came back some distance to a good farmhouse, whose outlines I had previously seen. The family were at breakfast, and after explaining that I had started from Chagford, intending to walk to Tavistock. I expressed a desire to hire a vehicle, as I had hurt my foot. The farmer agreed, and pressed me to take some breakfast, a request I complied with, and so satisfactorily, that my host complimented me on my appetite. As we drove back towards Princetown we met some mounted guards, who questioned me about my other self, and I had the pleasure of hearing a marvellous story of my own escape with two bullets in my body. I was now a respectably dressed member of society, having apparently nothing in common with No. 476′, the fugitive convict, yet in passing the huge building where I had spent some years, I could not help feeling considerable trepidation. Tavistock was safely reached, and the first South Western train took me to my native city.

I walked slowly down the street in which my home was. Suddenly my heart gave a jump, a mist crossed my sight, and I hardly had strength left to creep into a shop and drop on a chair. Opposite my house two men in plain clothes paced up and down, and one of them I recognised as a Dartmoor warder, who must have come up by the night mail. In truth I was nearly frightened to death, for if recaptured I should be flogged and obliged to go my whole term of imprisonment.

I at once left the place and went to an adjoining town where Ned Chambers and his father had a large factory. As I walked into their counting-house, Ned, who stood with his back to the fire, looked at me for a minute puzzled. “Oh Mr. – Mr. Boyle, how are you?” he said, with a glance at an elder man, who sat behind a newspaper. “Just step in here for a minute.”

To cut the matter short, there was a vacant clerkship in the establishment, which Ned, who never doubted my innocence, gave me, and I am now the principal cashier, with hope of a partnership.

Where is the moral of the tale one may ask? There is one, unfortunately for my peace of mind. The newspapers, in relating my escape, said I was traced to Cranmere Pool, where I was certainly drowned, but that this report was circulated for the benefit of those who might be tempted to follow my example was proved by the fact that my wife was haunted by detectives. Mine was the only successful escape ever made from Dartmoor, and I knew that the authorities would move heaven and earth to find me.

With Ned Chambers’ aid my wife and I met two or three times, but she was so closely watched that we feared to continue it. I became by degrees intensely nervous, made two or three efforts to leave the country – once by Plymouth, and again by Queenstown – but each time found, or fancied I found, a detective’s keen eyes upon me, and I sacrificed my passage-money in both cases rather than undergo the scrutiny any longer.

I live under an assumed name and am practically separated from my wife (who wears widow’s weeds) and my children. Friends are always chaffing me about my ‘hunted’ look, and with reason, for if I come suddenly upon anybody I fancy I see one of my former gaolers; the glance of a policeman terrifies me. Even at night am I pursued by dreams of being dragged back to Dartmoor, again clad in its hateful livery, and shrinking as the whip whistles over my naked body. The passing years have rather intensified than diminished this feeling. My nerves are shattered, my health broken, and I look twenty years older than I am.” – The Bideford Weekly Gazette, March 10th, 1891.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor