“Under the arms of a goodly oak tree,

There was of swine a large company:

They were making a rude repast,

Grunting as they crunched the mast,

Then they trotted away: for the wind blew high –

One acorn they left, no more mote you spy.”

There are a couple of adages regarding acorns, one being; “like stealing acorns from a blind pig,” which denotes something that would be simple to accomplish. The other age-old saying being; “from little acorns mighty oak trees grow,” and I think this should be amended to; “from little acorns mighty oaks trees and fat pigs grow.” As will be seen, acorns and pigs have for time immemorial have had a very close connection.

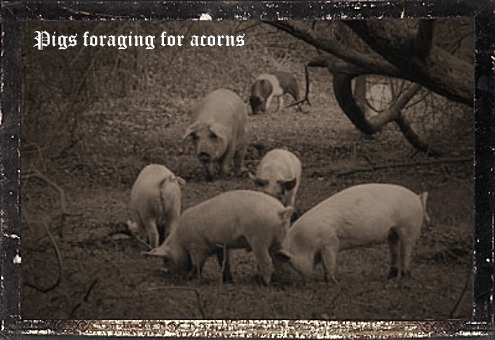

The right of ‘pannage’ has for centuries been given to the commoners of Dartmoor and basically this allowed them to turn their pigs into the woods to graze on the acorns and beech mast. There can be no question that this practice has been practiced on parts of Dartmoor since at least Anglo Saxon times. According to the Oxford English Dictionary the word pannage is derived from; “Late Middle English: from Old French pasnage, from medieval Latin pastionaticum, from pastio(n-) ‘pasturing’, from the verb pascere ‘to feed’.” Other Dartmoor place-names which could indicate the presence of swine are; Swinecombe, Pigshill Droke, Pig Lane, and Swine Down,

The ‘pannage months’ where when the acorns were ripe enough to allow the pigs to root and depending on the season could occur anytime between September and November.

In his excellent book about Dartmoor transhumance Harold Fox wrote; “Spitchwick, named in the Domesday Book… Its name is evidence for driving pigs to distant woodlands for the mast season and, presumably, for other forage before that time.” – p.153. The evidence for this in the place name comprises of two elements spic beaning bacon and wic meaning habitation or farm thus giving ‘bacon farm’ or a pig farm, p.528. The Domesday Book mentions that at the time the manor held one league of woodland, much of which still exists today. In many cases this privilege had to be paid for on an annual basis, the rents being due on or around Michaelmas. In the 1400s Tavistock Abbey was charging twopence a head for the rights of pannage on their lands. It is known from old abbey records that in 1413 the pannage of Parkwood was returning nineteen shillings a year. Finberg, p.132. This suggests that there were 114 pigs rooting around that particular woodland. In 1856 when writing about the Forest of Dartmoor in medieval times R. J. King noted that; “Great herds of swine were fed in the woodlands; and small huts ‘buricæ’ were built there for occasional shelter. Besides the ordinary swineherd, there existed Porcarii, or keepers, whom seem to have been free occupiers, renting the privilege of feeding large herds of swine in the woods, some for money and some for payment in kind. A Porcarius at Lidford, made an annual return of ten pigs to the Lord of the Manor.” p.92. Stanes notes how at the time of the Domesday survey in 1086 the county of Devon recorded the highest number of swine herds in the country. p.132. There are numerous medieval illustrations such as that which appears in the Luttrell Psalter which clearly show swineherds knocking down acorns for his pigs to feed.

It goes without saying that the ability to feed your pigs for free was a great benefit to the commoners of Dartmoor as well as providing the animals with a valuable source of nutrition. Many oak woodlands would have been within easy access for most moorland dwellers who were not backward in coming forward as far as acorn collecting went. In 1847 many of the crops which were used to feed pigs had failed miserably and to make up this shortfall pig keepers were advised to turn to acorns as a cheap alternative to expensive feed. It was stated that in a good year a single large oak tree would produce twelve bushels of acorns which would be sufficient to feed one porker without any other food. In the October of 1856 the following appeared in Truman’s Exeter Flying Post: “Acorns may be gathered in and laid by as food for the older pigs, from one or two quarts a day is a sufficient mixture with other food for each pig. The acorns are better for being kept a little while until they begin to sprout, in which state they make a much more wholesome food than if given when gathered in fresh, and as children may be generally found glad to pick up acorns for 1s. a bushel, a good deal of useful food may thus be added to the farm produce at a very cheap rate.”

So as can be gathered the feeding of pigs on acorns and has always been a part of Dartmoor life. Whether they were grazed in the woodlands or fed in domestic situations in the end the acorns led to valuable food source during the winter months. There are a few plus’s and minuses to pigs that rooting around on the woodland floor. One major plus is that acorns are highly poisonous to cattle and therefore by clearing the floor of acorns the pigs are lessening the chances of cattle dying from acorn poisoning. A minus point is that pigs can cause a great deal of damage to woodland by rooting, this could be overcome by putting rings through their noses during the time they are in the woods and then removing them when they are taken away. Additionally there are times when the pig’s fondness of acorns can land their owners in trouble with the law. There have been numerous cases where pigs have escaped in search of acorns and have been found wandering on the highway which was classed as a felony. Just one example being that of Issac Badcock of Roborough who in the November of 1881 was summonsed for allowing eight of his pigs to stray on the highway. His defence was that despite doing all he could to stop them straying they had broken through the fence and made off in search of acorns. The unsympathetic bench fined him 6d. for each pig plus expenses. In 1895 one Robert Ellis, a farmer from Hennock, was fined 7s. 4d. for allowing his four large sows to stray on the highway. Again his defence was that somebody had left the farm gate open and they had gone off in search of acorns.

There has always been certain circumstances when the country has faced times of strife no so more than in periods of war. It is during these times when vital food supplies have come under great pressure and demand dramatically increased. Not only was the extra food needed to feed the troops fighting in such conflicts but also maintaining supplies for the civilian population. During both the First and Second World Wars the humble acorn has played its part in the war efforts and not only as food sources. During World War One people were urged to collect hard nut shells as the Ministry of Munitions urgently required such things to make charcoal which was many times more effective than any other as a protection against poison gas. In 1915 the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries produced the ‘Special Leaflet No. 32. This advocated the formation of Village War Food Societies in rural areas. These would be responsible for such things as pig, sheep, cattle, rabbit and poultry keeping and the collection of acorns to name just a few. In the case of acorns these had to be fed with caution as excessive amounts can lead to acorn poisoning. In 1915 it was suggested that; “when acorns, in sound condition, are given judiciously, in small quantities only they are unlikely to cause any ill-effects, but are a valuable addition to the ration, more particularity in the case of pigs.”

Once again during the Second World War the call went out once again for children to collect acorns for feeding to the local pigs. It was quite noticeable how much there value had increased over the years. A bushel of good quality acorns had increased from three shillings a bushel to between five shillings and seven shillings and sixpence. “In Devon school children collect wild nuts to feed pigs and following the Board of Education’s announcement they will only be reviving a former custom of some villages. An old record of Cornwood school reveals that in about 1870 it was the usual thing at this time of year to give the children a few days holiday in order to harvest the acorns and beech nuts from the woods for the parish pigs.” – The Western Morning News, October 28th, 1939. Again in the same year another correspondent wrote: “It is much to be feared, that many tons of acorns are wasted in private woodlands where pigs are not allowed to run. This is particularly deplorable at the present time, for there is an obvious possibility of a shortage of the usual feeding stuffs, and pigs are among the quickest of all meat producers.” – The Western Morning News, October 20th.

Similarly in 1942 the Devon and Exeter Gazette carried this report: “The County Garden Produce Committee set up by the Ministry of Agriculture have been requested to organise the collection of acorns and beech mast. Pig and poultry keepers should make their needs known at once to the secretary of their County Garden Produce Committee… County Garden Produce Committee have been asked to arrange collection of these nuts where stock-keepers advise them that they would like to have supplies.” – September 18th, 1942. It was suggested that the prices charged for the acorns were 1s. 6d. a bushel or 3s. per hundredweight. Apparently Whiteways the Devonshire cider producers launched an appeal for collecting acorns. They owned a herd of 1,000 pigs to which they successfully fed acorns and so were advocating their use as a source of feed. They also added that the children of Whimple (where they were based) managed to collect seven tons of acorns. In 1944 the local Boy Scouts and Girl Guides along with children were organising acorn collections and by this year their value had risen to between 2s. 6d. and 3s 9d. per bushel and between 5s. to 7s. 6d. per hundredweight.

As far as the actual woodlands go it has been said that throughout history they have gone through three periods. Firstly where their main value was the food source provided for pannage and hunting, secondly their value came from the need for valuable timber in which to build ships. The third period was that of amenity purposes and game rearing and shooting. As private woodlands became increasingly important for valuable timber production less and less pigs were allowed to root amongst them. This saw an increase in the home-bred ‘cott pigs’ which were reared in the backyards of many moorland dwellings. To the best of my knowledge the only national park today where pannage takes place to any large degree is the New forest

OK, all the above was yesterday but what about today? One top chef who has worked at many of London’s top restaurants believes firmly in ‘Pannage Pork’, in his opinion; “pannage pork rivals the best in the world for its flavour and texture. As the pigs have been left to roam, the fat content seems to be a little less and the meat slightly darker and drier, with a more concentrated flavour. It’s extremely ‘porky and we always serve it medium and always very simply, to enhance the really excellent flavour. The second you put it in your mouth, you know the flavour is something special.” Today ‘The Old English Pig Company‘ at Leigh Farm, Bittaford produce pigs that are naturally fed and their diets supplemented with acorns from their woodland

By the way it’s said that a heavy acorn crop is a sign of a bad winter to come?

Finberg, H. P. R. 1969. Tavistock Abbey, Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Fox, H. 2012. Dartmoor’s Alluring Uplands. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Gover, J. E. B., Mawer, A. & Stenton F. M.1998. The Place Names of Devon. Nottingham: The English Place-Name Society.

King, R. J. 1856. The Forest of Dartmoor and Its Borders. London: John Russell Smith.

Stanes, R. 2005 Old Farming Days, Halsgrove Publishing, Tiverton.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor