“Such a vast bleak area of monotonous moorland, with scarce a house visible to cheer the solitude. Positively for miles you see no track of man on the moor. On the road across it we came to a small inn, where the horses were baited. Its name was ‘The Warren’ and on its painted signboard were three rabbits, sitting up with cocked ears, and facing each other, as if glad to have each others company and sympathy in the desolate wild.” – 1903.

Drive between Princetown and Moretonhampstead and you will pass what is possibly the most famous inn on Dartmoor. It is reputed to be the second highest inn to be found in England and is literally festooned with legend and traditions. So before things go any further there is something that needs to be cleared up, thanks to Andrew Hackney (see visitor’s book, 31/10/09) it can be confirmed that the Warren House Inn is in fact the 10th highest inn to be found in England. The name of this establishment is the Warren House Inn and it takes its name from the nearby, one-time Headland Rabbit Warren.

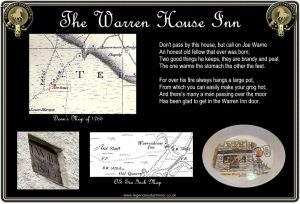

This however was not the original inn as a look below at Donn’s map of 1765 will prove. Today the inn is owned by the Duchy of Cornwall and is leased to the landlord, Peter Parsons. Sitting at an altitude of 424 metres the Warren House Inn is claimed to be the highest in Southern England. The Tann Hill Inn in North Yorkshire claims to be the highest in all of England at 528 metres. Although there have been many that have disputed this fact and falsely claimed the warren house to be the highest in all of England.

The first inn on the site was actually built on the other side of the road to the present structure and was known as the ‘New House’. It is thought that the first inn was built around 1760 which coincided with regrowth in tin mining in the area. The inn would have also serviced workmen and later travellers of the newly built Moretonhampstead turnpike road of 1772. Due south of the New House was a large rabbit warren which has also been called ‘New House Warren’. During this period the combination of mining activities, rabbit warrening, and passing travellers must have made for a bustling place. In 1831 the indomitable Mr and Mrs Bray passed by the New House and from all accounts was none too impressed. When going to tend to his horses he found the stable full of turf and remarked that the building had seen, “better days”. Sometime around this period the legend of the ‘Salted Down Feyther‘ became attached to the inn although some people will question whether its association is correct.

By 1834 the self styled ‘Dartmoor Poet’, Jonas Coaker had become landlord of the New House inn and by some reports it was not the most salubrious of places. On one occasion some miners became so unruly and began helping themselves to free drinks that Coaker had to flee the inn for sanctuary upon the moor, leaving the pub to run itself. On another occasion there was a fight which resulted in the death of a miner. But thanks to the evidence of Jonas who stated the killer was grossly provoked he was only sentenced to three weeks in prison.

In 1845 the inn moved location for during this year John Wills built a new building on the other side of the road. The inn was still called the ‘New House’ and tradition has it that from this date a peat fire was built in the hearth and has burned continuously to this day. The Sheffield Telegraph of the 7th of October reported how embers from peat fire at the old inn were carried across to the new premise and ‘like a phoenix rising from the ashes’ the now fabled ‘eternal fire’ was lit. The secret of keeping the fire burning was at each night to place the partially burnt out peat in the corners of the huge hearth then bury them in ashes. In the morning the ashes were removed and the partially burnt peat along with some charcoal and fresh peat was placed in the centre of the hearth and with the aid of bellow brought back to life again. Depending on what you read the claims for the amount of time the ‘eternal peat fire’ has been constantly lit vary from 100 to 250 years. Today the owners of the inn claim rather loosely that their fire has been burning since 1845 which would currently (2019) equate to 174 years. Today the fuel used for the fire is no longer peat but locally sourced wood. Maybe today the claim should be the fire that has burnt continuously since 1845 fuelled by local resources? There is a slate plaque on the eastern gable wall outside the Warren House Inn which reads, “L Wills – Sept 18th 1845” which clearly marks the completion of the new building and the opening of the inn – see below.

It was reported in the Exeter Flying Post that the February of 1853 saw a particularly severe spell of winter weather. At this time a couple had been married at Christow and following the ceremony had left with a waggon load of their possessions in order to move into a new house near Tavistock. The snow became that bad that having reached the Newhouse Inn they became stranded and ended up spending their honeymoon there.

During the 1850’s several reports were made regarding the behaviour of the miners with several fights occurring. It is also supposed that at this time the inn was also serving as a butchers shop, supplying both locals and miners alike.

On the death of John Wills in 1850 the inn, now called the Warreners Inn passed to his son John and it appears that the inn had become a collection point for deliveries of all kinds. It is thought that sometime during this period that the legend of the ‘Grey Wethers‘ had become attached to the inn. In the early 1850’s the actual landlord of the inn was Joseph Warne who the famous lines were written – see below. After the death of his sun relinquished the place to William Jinnings, sometime around 1857. Jinnings remained in-situ until 1861 when William Maddock succeeded him as landlord. In 1866 the Warne’s returned with Joseph at the helm. Still the in was much frequented by the miners and at this time there are a few reports of locals complaining they could not get a drink as the inn was packed full of tinners. In about 1874 a well noted occurrence happened when James Hannaford of Headland Warren was returning home from the inn. For some unknown reason he wandered to close to an air shaft near Hamlyn’s Gully and the ground opened up and swallow the unfortunate man. Luckily his fall was broken by some cross timbers about 14ft below the surface and it was on these that he spent the night. His faithful dog remained by the edge of the hole and it was by his barking that the rescue party were able to locate and extract poor Hannaford. In 1882 Joseph Warne died and Thomas Hext took over as innkeeper and he continued to welcome the miners to the inn. Things did not change and the inn was witness to many fights and quarrels amongst the tinners. By the very nature of the tin mines, men from all over the country came in search of work and this mixture of nationalities and counties meant there was always a ready spark for trouble. By this time the name – Warren House Inn was in wide usage as the Ordnance Survey map of 1888 clearly shows:

In 1898 John Wills II died and passed the lease over to his son John III who made a few minor repairs and allowed the Hexts to remain as landlords. In 1905 one visitor described the inn as being run by “two primitives,” and the room as being a flag floor upon which stood some settles and was warmed by a pear fire. An Inland Revenue survey of 1910 described the inn as being in a bad state of repair and noted that the ground floor consisted of a sitting room, taproom, kitchen and cellar whilst upstairs were 4 bedrooms and a toilet was outside in the yard. Plans for renovation were submitted to and were finally completed in 1914. During this period a clause had been written into the lease that if the Golden Dagger mine captain ever complained that his miners were incapacitated due to drink sold by the Warren House inn the tenancy would be terminated with three months notice. Records show that the miners were still causing trouble and one story relates how one miner called ‘Bill Mac’ was that drunk that he picked a fight with the large granite cross, presumably Bennett’s Cross which stands near the inn – needless to say he lost.

In 1915 John Wills the third died and left the tenancy to his daughters who consequently sold it to the Duchy in 1918. In 1921 William Toop Stephens acquired the tenancy of the inn where over the next eight years he managed to build a thriving trade from both the miners and the increasing numbers of tourists who were now driving out to the moor. Sometime in the 1920’s it became the norm to hold dances in the shed on the opposite side of the road, by all accounts these were popular events both among the Postbridge locals and the miners. Sadly in 1929 William Stephens shot himself in the bar and died immediately from his injuries. It was stated at the inquest that at 6.00 pm. the family had their dinner and Mr. Stephens, who had been drinking went into the bar and from behind the counter took down his gun which was kept on a nail. Mrs. Stephens, having followed him said to him that he didn’t need the gun. Mr. Stephens then assured her it was alright. and that the gun had been cleaned. At this point the gun was pointed at her although in her opinion not deliberately so she left the room. No sooner had she closed the door than she heard the sound of the gun being discharged along with breaking glass. The Stephens’ son also stated that he knew no reason why his father had taken down the gun as he had only cleaned it the previous day. He also noted that he did not see his father load it with a cartridge – the inquest’s verdict was “suicide during temporary insanity.” After this tragedy Stephens’ wife Mary carried on running the inn until 1930 when she left due to bad health. The next incoming landlord was Arthur Hurn who remained at the inn until 1951. If you look at the illustration of Mr. Warne below you will see what looks like two spaniels sitting infront of the fire. In the November of 1930 Arthur Hurn was summonsed before Mortonehampstead magistrates for allowing his two spaniel dogs to worry the sheep of farmer Perryman’s sheep., he was fined four shillings and promised it would never happen again. February of 1939 the Princetown to Mortonhampstead road had been blocked with snow for over a week. So desperate were the Hurn family for food and provisions that Mr. Hurn and his daughter rode fourteen miles on horseback to get supplies. On the 7th of March 1946 Mr. Hurn had some unwelcomed guests in the form of some escaped borstal boys from Princetown Prison. Once they had gained entry by forcing a downstairs window the offenders locked Mr. and Mrs. Hurn in the upstairs of the inn by locking the downstairs door. They the ransacked the sitting room and helped themselves to two cheque books, £6 in cash, clothing coupon book and some outdoor clothing. By the evidence it appeared that they had spent quite some time in the room as the oil lamp had been lit and allowed to burn itself out and large amounts of orange peel scattered all over. Much to the amazement of the Hurns they never heard a sound of the intruders and it was only in the following morning that they discovered the break in.

The postcard drawn by R. J. Dymond below dates from around 1935 and is said to depict Harry, alias ‘Silvertop’, Warne who was a regular at the inn, sitting infront of the ‘eternal flame’ in the bar. Tradition has it that he used to wear a bunch of ‘lucky’ white heather in his jacket pocket which at that time was something the tourists always wanted. It is said that if a visitor asked him to sell it he would at first refuse as it was a ‘rare’ thing. Eventually he would succumb and exchange the bunch for a drink and as soon as his customers had left the inn he would produce another bunch for the next gullible idiots. There was also a rumour that the reason he had a plentiful supply of white heather was because he would blanch the ordinary purple heather by putting boxes over it thus depriving it of daylight and turning it white.

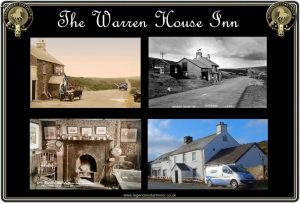

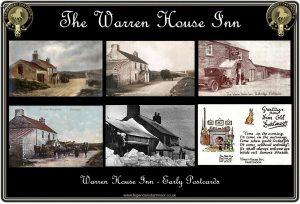

Above are a few old postcards depicting the Warren House Inn throughout the years. It is obvious from the one in the middle of the bottom row that winters were always something to contend with on this part of the Moor. One of the worst examples was the winter of 1947 when the inn was cut off for six weeks.In this selection of postcards you can also see the transition from the mode of vehicles used to transport visitors stopping at the inn, from the horse-drawn charabanc to the motor car including the horse drawn hay waggon. In 1922 that the Postmaster General publically gave notice of his intention to place a ‘telegraphic line’ of posts which ended at the inn.

Another final near to the inn is linked with the story of Jan Reynolds are the Aces Fields which lie opposite the Warren House Inn. Another version of how these enclosures came into being is that two miners were playing cards at the Warren House Inn. After a while one of them bet the last of his money on a ‘dead certain’ hand and lost the lot. This annoyed him so much that he built the four ‘card enclosures’ as a reminder of the money he lost and the foolishness of gambling.

In letterboxing circles you may occasionally hear mention of the ‘Eight Lions’ which refers to the eight concrete lions that support four benches in the beer garden of the Warren House. It is amazing from how far away they can be seen, hence they have been used in letterbox clues.

So if ever you are passing the Warren House inn why not drop in, you won’t find Joe Warne there anymore but there’s still; “Many a man passing over the moor, Has been glad to get in the Warren Inn door!“

Greeves, T. A. & Stanbrook, E. 2001 The Warren House Inn, Quay Publications, Brixham.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor