Having recently spent the night at the Two Bridges Hotel it was fascinating to come across this story of another guest who stayed there 122 years ago and the reason for his vacation. Back in those days there was a consensus of opinion that many ailments could be cured by huge doses of fresh and healthy air. Probably the biggest influencer in this was the respite gained from escaping the polluted atmosphere of the towns and cities. It can be said that today there is still a benefit from escaping the air pollution and possibly add the benefit of escaping the daily pressures of life. So where better to get such a tonic than the ‘Lungs of Devon,’ AKA Dartmoor.

“You look seedy – run down, my dear fellow – you should go up on Dartmoor; you will find the air up there a wonderful tonic, I can assure you.” Thus I was addressed by several friends about a month ago, when sorely troubled with unwelcome visitors in the guise of tormenting, irritating boils, which settling themselves in rapid succession upon my neck and head, had clung to me with a pertinacity equalled only by that with which a limpet clings to a rock, and necessitating the casting aside of the well-starched high collar, the pride of every well dressed Briton, and the substitution of a soft silk muffler, which, to my mind, is suggestive either of a confirmed invalid, which I was not, or of an athlete in training for some big event.

If I remembered them all, I dare not recount the numerous remedies recommended to me. There is, however, one remedy for boils, blackheads, etc, told me in all seriousness. I was told that I should into the country and search for a bramble, a branch of which had overgrown, and, drooping towards the earth, had taken root again in the ground. When such a natural arch was discovered, I was to go down upon my hands and knees and crawl three time – neither more nor less – underneath it, and I would be forthwith cured, and never again be troubled with such acquaintances. And we live in a civilised age!

It was not until the last Friday in March that I took my my own prescription, and with some misgiving, for wet days were being sandwiched between fine ones with a remarkable degree of regularity, and made tracks for the moor.

FRIDAY.

Two Bridges Hotel, in the neighbourhood of Princetown had been recommended to me for its comfort and location, from 1,2000 to 1,400 feet above the level of the sea, in the midst of wild and romantic scenery, and thither I resolved to make my pilgrimage. The thought occurred to me that whilst there I should like to see the interior of the great convict establishment, and asked a friend of mine, learned in the law, which was the best way to get into Princetown Prison. He smiled, not the smile that is childlike and bland but the smile ironical, and said he thought that the easiest way to get into Princetown prison was to commit a burglary. I explained that I did not want to take up permanent residence there, only to pay a fleeting visit, and had imagined that a visiting magistrate could favour me with the necessary passport, but my legal friend assured me that the only person in the land who could give such authority was the Home Secretary.

Princetown has a railway station, and consequently has a railway time table, and there I sought it. The information gleaned was that there were only two trains a day available from Torquay at this season of the year, and although Two Bridges is only 25 miles from Torquay, as the crow flies, I found the railway journey, with the delay at Plymouth, occupied nearly four hours. Here I ought in fairness to interpose and state that in the summer coaches run from Moretonhampstead to Princetown four days a week, offering a much more enjoyable route, and that the train via Plymouth are then more numerous.

I arrived at Princetown about eight o’clock in the evening, found a wagonette outside the station in which to be driven to Two Bridges upon as dark a night as ever travelled out in, and so dark that I was unable to distinguish the road from the boundaries. The driver fortunately was familiar with the road, and we reached the hotel in safety, and I found a comfortable room, a hot dinner and a hospitable welcome awaiting me. Both Mr. and Mrs. Trinaman manifest a tender solicitude for the comfort of their guests, and at this high altitude, and with a strong wind blowing, I was pleased to find a fire in my bedroom. The wind rose as the night advanced, it whistled and hissed and roared around the hostelry to such a degree that all the comfort that man can devise could scarcely induce sleep under such conditions; and I lay awake for some hours listening to the fitful fancies of the wind, now lulling into soft, soothing, almost caressing cadences, and then breaking out into loud boisterous railings, and raising my doubts and fears as to the weather in store for me during my all too brief holiday.

SATURDAY

The morning broke ominously; the wind was still high, and portentous clouds drifted across the sky, but there was no rain; and after breakfast I set out for my first walk, going in the direction of Princetown. Before reaching the prison I met small bands of convicts, a party of eight drawing an empty cart being in charge of a warder, who carried a rifle, whether charged with a bullet one cannot of course say. The grim, great gateway, constructed of huge blocks of granite, the keystone of the structure bearing the inscription, “Parcere svbjectis’ (To spare the conquered (vanquished); placed there presumably, when erected nearly a century ago, and when occupied by many thousands of French prisoners of war, attracted my attention. Continuing on my walk I attained higher ground and could look down upon the prison yard. A big detachment of convicts was coming from the fields, and I saw them enter the prison yard like a battalion of infantry, disappearing around one wing of the buildings. A sentry posted on a watch tower began waving his arms in my direction, and I feared he was warning me from my post of vantage, but he moved at once to a semaphore and made a signal. Turning around I saw the signal answered from a watch tower which commanded a quarry where convicts had been working, and shortly afterwards met a warder clothed in a mackintosh and carrying a rifle, and as the first sentry had quitted his post, I concluded that the operation which I had witnessed was simply signalling No.2 off duty. From him I learnt that being a Saturday, the convicts had then, at eleven o’clock, completed their farm and quarry labour for the day. Returning about half an hour later, a large number of warders were leaving the prison, having also finished their duty. I walked by the side of one, upon whose shoulder-knot were the initials “C.G,” which I interpreted to mean “Civil Guard,” and though doubting whether I was within my civil rights, I ventured to put to him a question, and he answered me quite civilly as becomes a Civil Guard. I inquired how many convicts were at the present in the prison, “Handy on to a thousand,” was the prompt reply. “And how many warders? was my next query, “About two hundred,” he said. “You must find the air very bracing and healthy here,” I suggested. “Well,” said he, “it’s bracing enough, but I don’t know about it’s being healthy. It’s the way, you see, the sharp, keen air gives you a big appetite and not getting sufficient exercise – I am in the stores – which is why you get indigestion.” We had then reached his house and we bade each other, “good morning.” I made for my hotel, reminiscing as I walked briskly along upon the sad world that was shut up by those dark high walls. I also realised that the keen mountain air had also given me a big appetite, but I was taking all the exercise the elements would permit, and so escaped the civil guard’s experience of dyspepsia.

After lunch I went for a long walk on the Moretonhampstead road and inflated my lungs with the pure moorland air. Breezy, bracing, aye, even bleak, Dartmoor is a perfect sanatorium for those who live in the soft, sometimes enervating air of the lowlands. This vast expanse of moorland, which has an area of 200,000 acres may be regarded as “one of the lungs of Devon,” and with the license that is extended to metaphor, we may speak of its other lung as the sea, that encircles its coast, time spent upon which or upon its shores being equally health promoting and life inspiring. How I enjoyed that walk; how elastic seemed my step; how delightful it was to be “far from the madding crowd,” and to listen to the song of the lark as he soared aloft, to admire the grandeur of the undulating moorland, its numerous tors, surmounted with huge rocks of granite, the formation of which would require but little stretch of the imagination to liken to fortresses; and to have faith in the recuperative properties of its pure and unadulterated air.

Returning home – to my hostelry I mean – in the evening with another “big appetite” for dinner, Trinaman’s menu proved equal to that of a first-class hotel in any city or town. I enjoyed that dinner as I did the lunch, and again did not suffer from indigestion – the physical exercise saved me.

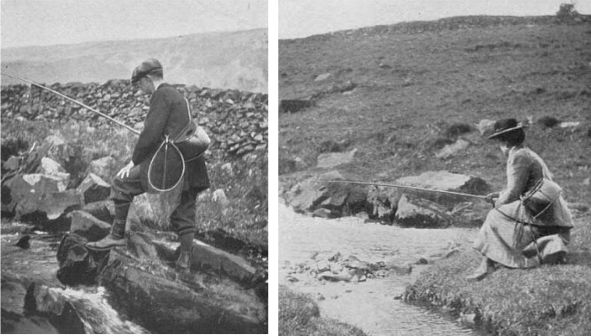

There were six or seven other guests, three of whom were gentlemen, and with them I spent the evening in the smoke room. They were ardent fishermen, and the enthusiasm they manifested showed that angling must be a fascinating sport. their talk was of the number of trout they had taken from the river close by, of the properties of artificial flies, and the merits from the angler’s point of view of different streams, and one realised how much they knew of a sport which is as old as the hills, and how ignorant was I. Some of their sayings were indeed to me quite mysterious, “A blue upright with a partridge hackle,” was a fly, an artificial fly it is true but still a fly from the sportsman’s point of view, “Wickham’s Fancy,” was a very killing fly, and “Garden flies,” was a fisherman’s pretty way of speaking of worms. Days upon the moor are proverbially long, but they have an end, and bedtime came, and I retired to rest and slept the sleep begotten of fatigue.

SUNDAY.

Though the wind lulled during the night, and raised hopes of brighter weather. an early peep from the bedroom window on Sunday morning was most disappointing, for Dartmoor had assumed a mantle of mist, at times as impenetrable as a city or town fog, but possessing little or none of its injurious consequences, for a moorland mist does not effect the respiratory organs as do city fogs. The mist floated over the moor in light, fleecy clouds, encircling in vapoury wreaths the rock-capped tors, and rolling in successive volumes across the undulating moorland, gathering moisture as it travelled, and distilling a fine, small rain of so insidious a character that it quickly saturates the clothes of those who venture forth in a Dartmoor mist, or should be overtaken by one. The mist continuing throughout the forenoon frustrated my plans, and prevented my visiting Princetown church, as I had intended. After lunch, though the clouds presented a threatening aspect, a patch of blue sky ever and anon presented itself, and invited one forth to inhale the pure, unadulterated, and vigorous air. Within a quarter of an hour’s walk of the Two Bridges Hotel, and at a loftier elevation, was a long stretch of table-land, and here for about a couple of hours I walked up and down, much as a sailor walks the quarter-deck, but my “quarter-deck,” was more expansive than the quarter-decks of all the navies of the world combined. How exhilarating was that walk; tho, one’s lungs seemed, as it were, to feed upon the pure oxygen which inflated them. It was well that I ventured not further, for a storm of this fine rain began to descend, and counselled my hasty retreat to the hotel, recalling the following humorous satire on the frequency of rain in some parts of Devonshire:-

The south wind blows and brings wet weather,

The north gives wet and cold together;

The west wind comes brimful of rain,

The east wind drives it back again;

Then,if the sun in mist should set,

We know tomorrow must be wet;

And if the eve is clad in grey,

The next is sure a rainy day.

MONDAY.

This was the last of the three days which were to make my present holiday, opened brightly and promising, and I was early astir, and eager to be out, long before the gong sounded for breakfast. Very shortly after the substantial meal, I was breasting the hill infront of the hotel leading onto the Tavistock road, along which it was my intention to take a three or four mile spin. With an elastic step that surprised almost as much as it pleased me, I found myself reaching level ground trotting along at a brisk pace, revelling in the bracing and invigorating properties of the Dartmoor air. A gang of about a hundred convicts at work in a field attracted my attention. At a given signal they ceased work, the unhappy men formed up two deep, and the armed warders, who had been on sentry, closed in around them as they marched off in the direction of the prison. Looking upon the gaunt, grey structures – for the prison is made up of numerous huge buildings – encircled by a high boundary wall which is said to be a mile in circumference. I reflected upon the sad monotony of the life of a convict, but that there are occasions when some of those in durance vile are moved by a spirit of humour, an extract or two from verses entitled “The Lay of the Lagged Minstrel,” recently written on his slate by one under detention at Dartmoor Prison, will show. These verses appear to have been written shortly after the escape of the convict Goodwin, who, it will be remembered, was shot by one of those warders. The poet assumes that Goodwin’s dash for freedom just before Christmas was that he might obtain more seasonable fare than that which the prison dietary affords, and which according to his rhyme, is not of a very inviting character. (the term ‘duff’ is prison slang for Plum Duff, a pudding served instead of Christmas Pudding). In a vein of irony the prison poet wrote:-

Sometimes, when things are very dull, a convict makes a dash

To gain his freedom, but the guards of him soon make a hash;

Lag shooting is such good sport – it’s never out of season –

But to shoot a pheasant in July is almost worse than treason.

The fame of English convict duff in known both far and wide,

From San Francisco to Hong Kong, from Melbourne to the Clyde;

It’s utilised for building ports, and ironclads as well;

It’s guaranteed to be bomb proof ‘gainst bullets, shot and shell.

Beyond its health-giving properties there was very little of interest in my morning walk, and returning to the hotel a brief respite from the mountain air sufficed for lunch, and I was quickly out again threading my way along a devious and very irregular path by the river, which, , within a hundred yards of the hotel, presents a picture, the beauty of which it would be difficult to excel, and the attractiveness of which must be greatly enhanced when the trees that line the banks are in leaf. The bed of the river is strewn with boulders, over which the stream, rendered lively by recent rain, bubbled and flowed, forming here and there miniature cascades, who falling water glistened in the sunshine. On the western bank of the river, and about a mile to the north of Two Bridges is Wistman’s Wood, which is supposed to have been one of the sacred groves of the Druids. The ascent to it is strewn with masses of granite, partly covered by a grove of dwarf oaks, so stunted in their growth by sweeping winds, that few are more than ten or twelve feet high, but their branches spread far and wide, and are gnarled and twisted in a fantastic manner, (slight error here as the wood is on the eastern bank of the river).

My last day’s tramp came to an end far too soon. Returning to the hotel a pretty English scene presented itself, a large party of huntsmen and women, who had been out with the Lamerton hounds had arrived, and the dead body of a fox lying across the haunches of the horse of one of the huntsmen indicated that they had had what in sporting parlance would be regarded as a “good day.” Before taking my departure from the hospitable Two Bridges Hotel, the liberal catering and excellent cuisine of which establishment are a revelation for moorland hotels, the visitors book was submitted to me that I might inscribe therein my autograph. Visitor books are invariably amusing reading and turning over the leaves of this one several interesting entries were revealed. “Came for a fortnight, and stayed seven weeks – volumes could say no more,” was a splendid testimony, alike to the moor and the hotel. The young lady who wrote the following, little realised the snobbish criticism to which it would be subjected: “Miss Rose L – Very nice indeed.” It was certainly somewhat vague; and a wag had written alongside in pencil, “Query, hotel or Miss Rose L-.” J. E. Muddock, the well known novelist who writes under the nom de plume of Dick Donovan, and was at Plymouth and Torquay with the journalists in the autumn of 1895, expressed his appreciation tersely as follows; “An excellent hotel, and an excellent host.” A couple who had made a prolonged sojourn, wrote; “After a fourteen week stay, have no hesitation in saying that anyone who cannot make himself comfortable at this hotel ought to be boiled.” Alongside this is inscribed the following commentary: “A Bishop, a Banker, a Merchant, and a Doctor wish to know is this telegraphee or English.” But the humour of the visitor book critic is a sorry wit, and I refrain from giving further extracts from those marginal notes and commentaries.

I was soon on board the train at Princetown, and with a change at Yelverton and another at Plymouth, Newton Abbot was reached at 9.30 with the unpleasant realisation that here intervened a wait of two hours before the journey to Torquay could be resumed. Fortunately I had with me one of Thomas Hardy’s novels, and before a fire in the well lighted waiting room the two hour’s delay was not so wearisome as it would otherwise have been. Shortly after midnight I reached home with the happiest reminiscences of a very brief holiday at Two Bridges.” – The Torquay Times, April 9th, 1897.

As with many of these old accounts there can be a tendency to waffle on somewhat but you can always get glimpses of times gone by which will never be witnessed today. It is clear from this narrative how much the author appreciated the fresh, invigorating, fresh air of Dartmoor. The writer also gives a brief glimpse of a Victorian Two Bridges Hotel with a fire in the room, a gong being sounded at meal times and the sporting clientele. You certainly will not see members of the Lamerton Hounds with dead foxes draped over their mounts and in all likelihood fewer fishermen. The various scenes witnessed on and around Dartmoor Prison will no longer be seen and the extracts from ‘The Lay of the Lagged Minstrel’ are an excellent insight to life in that prison.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor