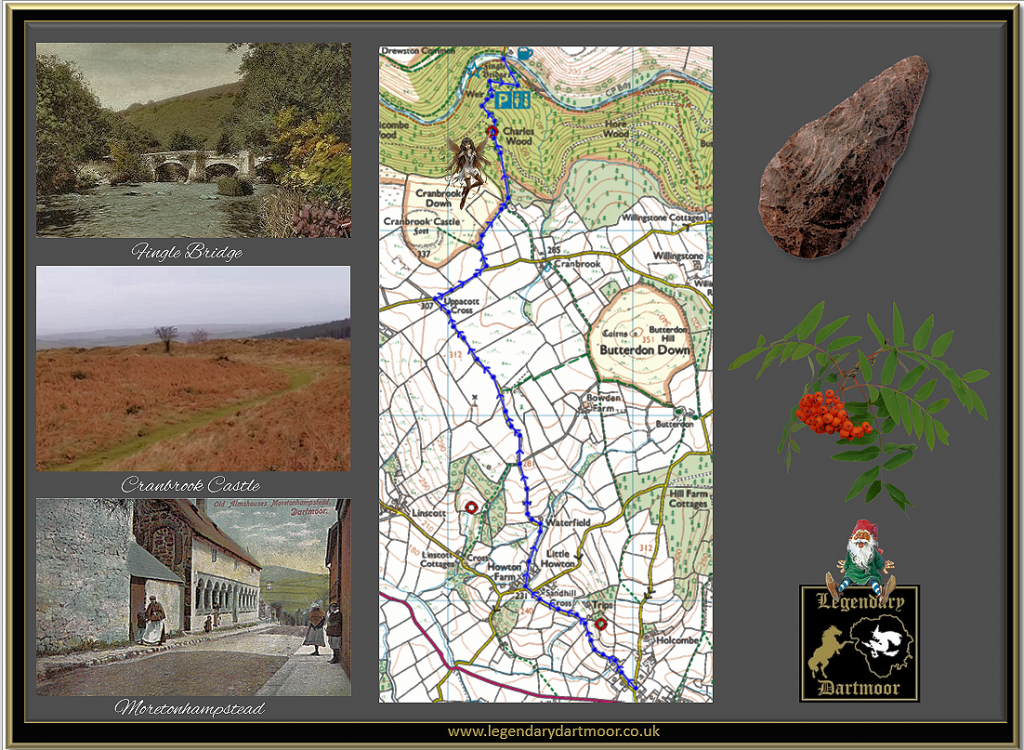

It is amazing the advances in archaeological technology have made all of which help to discover and research artefacts from times gone by. But who would have though nearly one hundred years ago some archaeologists employed the powers of Dartmoor’s piskies to lead them to amazing relics. How did that work you may ask, simple by being piskie led is how. In the February of 1938 Mr. Basil Barnam, a member of the British Archaeological Association set out from Moretonhampstead with the idea of walking to Fingle Bridge. Little did he know that on his way he would meet up with the fabled little folk of Dartmoor…

“It is a wonderful road, that road which leads to Fingle Gorge, and the brawling river under the wooded. Rock-strewn hills; a road between high stone walls grown over with the tiny Devon ferns and with, here and there, thick hedges of lustrous black holly and red-berried mountain ash; a road smothered with foxgloves and harebells and tiny blue flowers, whose names I have never known, and wild snapdragons, and rich red bell heather and the less vividly coloured heather that crowns the inner tors.

A lane deeply rutted and worn with a thousand years of travel and a thousand million footsteps; with milestones that were grey with age when they fired the beacon on Bellever Tor to tell the Exmoor men that the Armada had been sighted.

And because my thoughts were far away the piskies came over the hills, chortling with joy at my deliverance into their hands, and they led me until when I woke from my dreams, I found myself on a wild part of the Moor where I had never been before, knee-deep in bracken and heather, with the intoxicating smell of the gorse blossom stinging my nostrils. I wondered greatly as to how and when I had left the road. Over to the north I could see Dunkery Beacon looking out over the Bristol Channel; behind the valley that shelters Okehampton, Yes Tor rose black against the setting sun. On a distant hill were the giant rocks of Willingstone, and beyond the valley in which lies Moretonhampstead, the bleak summit of Easdon Tor rose towering to the sky. I knew where I was. What puzzled me was why I had been led to the place.

Just beyond a belt of bracken I came on one of our Moorland trackways, made by the ancient people three thousand years before the Saxon came to England’s shores. The bare patches of rock, that fine close growing turf that joined them told me that. And the track led me up the hill, up the bleak, bare, side of the hill till I came to the great ditch, with the double line of stone banks beyond that marked one of those giant fortresses which the men of the New Stone Age raised to defend their hill country from the invading Celt.

It was an amazing work. The ditch was twenty feet across, cut in the solid rock. Behind it rose two tiers of banking built up of the stone upcast from the ditch and of boulders gathered from the hillside. The first rose a good twelve feet from the ditch, and the inner one towered six or eight feet above that. Tens of thousands of tons of stone must have gone into their making, with years of labour and ceaseless toil. With what amazing military skill had these prehistoric engineers planned, laid out and executed their work.

I wandered over the six or eight acres within the walls seeking, but in vain, for some traces of the old inhabitants; thinking to find, perhaps and arrowhead or some fragment of pottery that would tell some story, however slender, of the men who manned this mighty work; a work compared with which, as regards magnitude, the great ruined cities along the Northumberland Wall pale into insignificance.

Then the piskies led my feet across the turf to the great west gateway, protected by an outer ramp against an invader’s charge, and, from the gate round the outer walls, to a place where great Dame Nature had left bare, untouched by vegetation, the grim, grey work of the long-dead hands.

There, lying at my feet, was a great stone axe weighing some eight or nine pounds, ground away almost to a knife edge, and as perfect as the day it was made, save for a frost flaw at one corner. I stooped to pick it up. I would have taken it back to London and shown it to my friends with pride, and, perhaps – I only say perhaps – have given it to some admiring museum. Ans as I stooped a piskie spoke to me; very solemnly and so quietly that I could only just catch its words; “He died for his faith; his home; his country and his loved ones. That axe is his only monument.” I looked again at the mighty axe that had lain there for many thousands of years. It was a very fine specimen; so perfectly ground. For aught I know, it lies there still. The piskies led me, full of thought and careless of my steps, back to the road to Fingle Bridge.” – The Torquay Times, February 18th, 1938.

Although Mr. Barnham never mentioned the fort by name it is pretty safe to consider it was Cranbrook Castle which is an early Iron Age hillfort. – “Cranbrook Castle Hillfort. This monument includes a slight univallate hillfort situated on the summit of Cranbrook Down overlooking the River Teign. The hillfort survives as a square enclosure measuring 160 metres across internally. It is defined to the north by a single rampart. To the east, west and south is a substantial rampart bank with a stone core, some stone revetment and a deep outer ditch. Whilst to the south and south west only is a further ditched counterscarp bank. There are two entrances to the interior, a simple gap with causeway to the east and to the south-west a causewayed gap further protected by a curved extension to the ditched counterscarp bank. The differences in the nature of the defences to the north and south have been attributed to different phases of construction rather than a response to the topographic location of the fort. Partial excavations in 1901 by Baring Gould of two hut circles on the eastern side of the hillfort interior produced some pottery and part of a rotary quern, although these features are not visible as earthworks. Cairns within the northern part of the hillfort are thought to be clearance cairns from past cultivation of the interior.” – Historic England, 2021, National Heritage List for England, 1003860 (National Heritage List for England). SDV364016. Maybe a good idea to notee that when Mr. R. H. Worth discovered the pottery and part of a quern he found them without the help of the piskies.

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Legendary Dartmoor The many aspects past and present of Dartmoor

Wonderful articles. Thanking you from the States. Would like to visit someday.